Cyber security leaders have to be effective change agents to be successful. Cyber capability uplift and risk reduction initiatives often require significant transformation in the organisation. In this blog, I’ll introduce a tried and tested change management framework and demonstrate its application to cyber security in an illustrative case study.

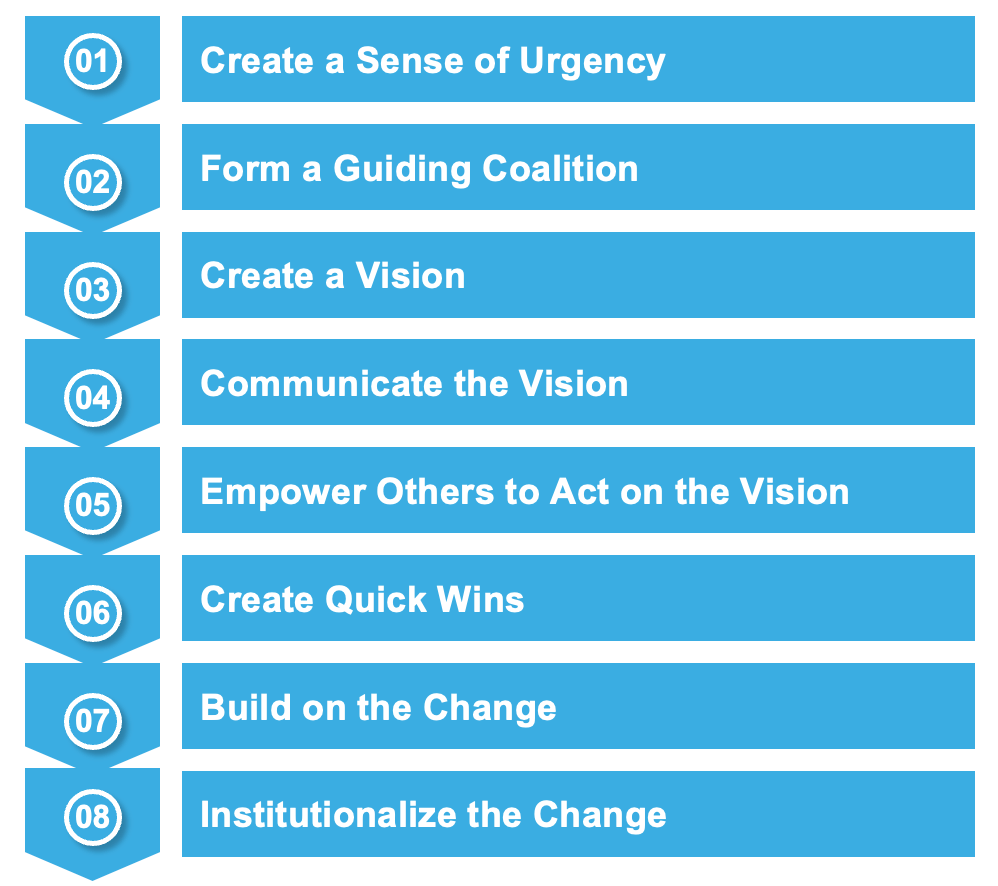

As a cyber security leader, imagine for a second that you identified an improvement opportunity to uplift cyber capability in your organisation. As this is likely to be a significant change, I recommend following Kotter’s 8 steps (Kotter 2007) to increase the likelihood of success. Given the sensitive nature of this project, careful planning and risk management activities are essential, particularly in relation to ethical risks.

Undeniable sense of urgency, powerful guiding coalition and clear vision can help set a strong foundation and will allow for early quick wins to be achieved to elevate the security posture. Although more work is likely to be required to institutionalise the improvement, this initiative will establish a momentum to continue to build on the change.

Transformation process

Step 1 – Create a sense of urgency

Many organisations haven’t experienced a major security incident in the past several years. However, the threat landscape is constantly evolving with cyber attacks becoming more targeted and sophisticated (Forbes 2023). To keep pace, defences need to be uplifted and new security controls implemented.

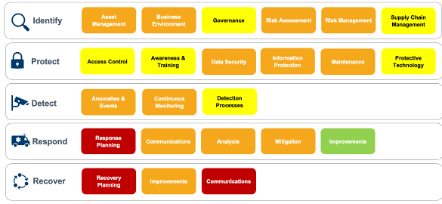

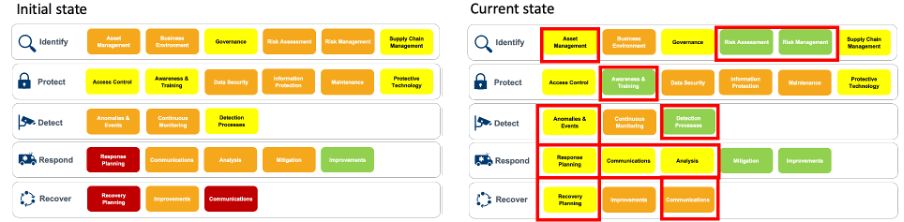

The absence of data breaches can create a strong sense of complacency among executives. To get people out of their comfort zones, I suggest commissioning an independent security assessment of your security capabilities (Figure 1).

Red and orange zones highlight critical deficiencies – the fact you haven’t been breached can to a large extent be attributed to luck. I suggest presenting the report to the executive leadership team: the case for urgent action becomes clear and maintaining the status quo is no longer a viable option. If applicable, reiterate your company’s role in the in the wider ecosystem as part of critical national infrastructure and the fact that attackers increased the level of capability and broadened their targeting (Forbes 2023). Leverage the external party report for added objectivity which helps avoid the ‘shooting the messenger’ fallacy, as these findings are coming from an independent credible source.

Emphasise ethical leadership aspects and values (Hughes 2016). In your discussions with the leadership team, remind them that effect on victims of data breaches can be shattering, including fraud and mental health impacts. Help them see the organisation’s wider responsibility – to protect your customers’ data. This ethical lens helps reinforce the need for urgent action.

Step 2 – Form a guiding coalition

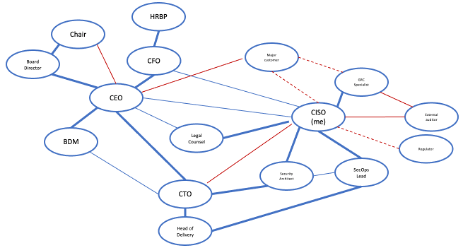

Conduct network structure assessment and willingness-value analysis of stakeholders (use Figure 2 as an example). This will reveal key stakeholder relationships and power structure in relation to this initiative highlighting tension (red lines) and indirect relationships (dotted lines).

This analysis informs the choice of key people to include in the guiding coalition. For example, you could form it with CEO, CFO, CTO, Head of Delivery and Legal counsel. If possible, request the CEO to sponsor the initiative and dedicate a session during leadership workshops to develop a shared understanding of the current state of your security capability. This also helps build commitment and further develop trust and communication between coalition members. Ideally, all of you share the sense of urgency and feel accountable for improving the security maturity.

Including a representative from the Board, the key customer and possibly regulator would improve the strength of the coalition. At a minimum, agree to provide an update to the Board once some changes have been implemented to demonstrate progress.

Step 3 – Create a vision

Co-create a vision statement during the leadership workshop with input from all guiding coalition members. It must be aligned to the overall business mission and purpose.

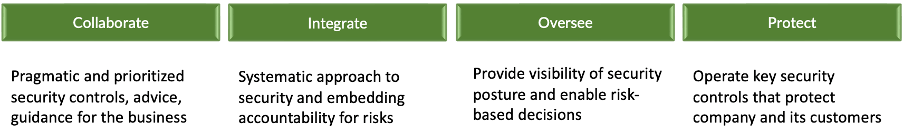

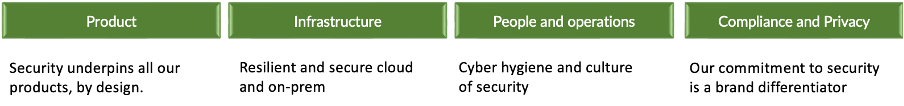

The pace of change of technology, threats and regulation means that the initiatives supporting the vision need to be agile. For example, you can base the vision and initiatives on the following guiding principles and focus areas (Figure 3).

If possible, it can be beneficial to get some input from the external auditor, regulator and a major customer as key stakeholders. If this is not achieved due to time constraints of the change, it can create a risk of limited buy-in. To mitigate, seek their input at a later stage. Assess other ethical, cultural and sustainability risks and considerations as in the example below (Table 1).

Step 4 – Communicate the vision

I recommend applying Authority and Social proof principles (Cialdini 2001) by getting the CEO to endorse the vision and demonstrate their support for the initiative. I also suggest adding this vision statement to every presentation deck and update you provide. To maintain momentum and diversify communication channels, organise for the vision to be included in the monthly newsletter and added to onboarding materials for new joiners.

Be mindful and pay particular attention to how you construct the message and how it’s being received rather than solely focusing on quantity (Hughes 2016). For example, try visually articulating the desired target state and what it means for people in your communications, bringing them along on the journey (Figure 4).

You know you’re on the right track when you start observing the product managers role-modelling the vision and leading by example in the product backlog review meetings, where they prioritise security improvements to the product over other functionality which may be competing for limited resources.

Reflect on your communication style. People with a technical background, like myself, tend to adopt a rational approach, focusing on facts. You could experiment more with inspirational appeal (Yukl 2008) to increase your impact through appealing to people’s hearts as well as minds to increase the likelihood of change being successful (Kotter, Akhtar & Gupta 2021).

Step 5 – Empower others to act on the vision

Security can often be seen as an obstacle because it can create friction with core business processes. Your aim should be to uplift security while enabling business agility. If possible, form partnerships with Product and Technology leaders to understand common pain points where security gets in the way of productivity. For example, I once identified a policy that was overly restrictive without adding security benefits: people were asked to change their passwords too often. I simplified this policy with no negative impact on security posture. This small yet significant change reduced the ongoing burden on employees and served as a signal that people’s concerns were heard. Are there similar opportunities in your organisation?

Anticipate more barriers to be identified as your program progresses and aim to remove these to empower people to experiment, encourage two-way communication, build buy-in and keep moving forward.

I often find one barrier that can’t be fully addressed in this type of project is some stakeholders’ attitude towards this change. Although not actively blocking the project, they may not be viewing it as a priority. To tackle this, I recommend asking for the CEO’s support to speak with the individual to make sure their cynicism doesn’t spread to the whole company and jeopardise the change effort. The key learning is the realisation that people, not only processes, can be blockers. Decisive action is needed to enable others and preserve the credibility of the project.

Step 6 – Create quick wins

Proactively plan milestones and tangible improvements in security posture to maintain momentum. Developed a plan (example is Figure 5) that can help the change appear less scary and more manageable.

It’s common to struggle initially to articulate quick wins. I recommend outlining smaller deliverables that serve as low hanging fruit for most initiatives. Such reframing allows you to create tangible milestones and communicate broadly about reaching them.

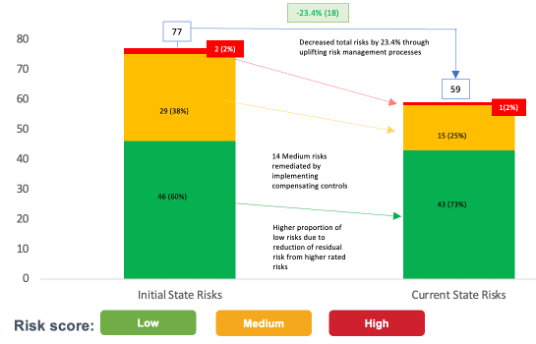

For example, if you updated your risk management process document and launched a new version of the risk dashboard, take your team out for lunch to celebrate. Several weeks into the project, you should be able to demonstrate the progress visually, building on the initial current state assessment in Step 1 (Figure 6).

This increases the credibility of the project, brings more people onboard and shows to the wider stakeholders that change is possible.

To make quick wins feel more impactful, make them more relevant for the business stakeholders. Some of the documentation developed as quick wins, despite being a necessary stepping stone, may not be perceived as the groundbreaking capability uplift some stakeholders are expecting.

Step 7 – Build on the change

Use the momentum generated by quick wins to tackle harder, more complex security initiatives, like uplifting the detection and response capability and implementing technology solutions. Be mindful not to declare victory too soon, so keep emphasising the sense of urgency by reminding people of the threat landscape and potential risks. This can be achieved by regularly briefing the executives on the current threat profile, key risks and the state of our uplift initiatives (Figure 7).

Overall, the approach is primarily focused on repeating the vision and the application of Leadership tools from the Organisational Change Agreement Matrix (Christensen et all 2006) which assumes consensus that this change is consistent with organisation’s ethos. You could also experimented with Power tools, like coercion, to influence indifferent stakeholders who didn’t believe this change was necessary.

For example, you could been more directive in your approach and assign risk ownership to stakeholders making them formally accountable in the event of a breach. You could also escalate the matter to the Board and threaten disciplinary action in the event of non-compliance. The aim is not to overuse these tools but to have a wider range of available options to affect change.

Step 8 – Institutionalise the change

Initially, you may not yet able to fully embed this change in the company culture. The focus should be on demonstrating to the executive team that new approaches and behaviours can lead to improved financial performance (Figure 8).

You can also articulate material risk reduction as a result of the implemented quick wins (Figure 8). This demonstrates that cyber capability uplift reduces overall likelihood and impact of potential security incidents and minimises your chances of being hacked.

Going forward, you can apply institutionalising change methods (Johnson, Scholes & Whittington 2008) to continue to ingrain new security attitudes in organisational culture. I suggest to focus on the following next:

1. Control systems: develop and enforce KPIs for executives to manage cyber risks, make acting in line with new values of protecting sensitive information a requirement for a promotion, embed security responsibilities in people’s job descriptions, incorporate questions about risk and security culture in the recruitment interview process.

2. Rituals and routines: add a security sharing moment to the agenda of every Town Hall meeting going forward, offer an opportunity for interested staff to be upskilled on security as a professional development benefit.

3. Stories: organise lunch and learn sessions to tell stories of near misses and data breaches in other companies and what we can learn from them.

Conclusion

Cyber capability uplift is necessary to protect people’s data and reduce the likelihood of data breaches. Despite being an ethical obligation to your customers, this change in itself has ethical, cultural and sustainability implications due to the use of technology that can be perceived by employees as enabling unfair surveillance and high energy consumption; these risks can be assessed and mitigated as part of planning (Table 1). One of the key learnings is the fact that a structured approach involving all of Kotter’s 8 steps (Kotter 2007) is essential for successful transformation.

Time constraints may create a temptation to skip earlier steps – surely the case for change was clear? I suggest to overcome this by remembering that avoiding steps only creates an impression of speed and can threaten long-term viability (Kotter 2007). Clear vision, stakeholder engagement, constant communication and demonstrated progress increases the credibility of the project and lays a solid foundation for this change to be institutionalised.

References

- AGSM UNSW Business School 2024, Disruption and Transformation, AGSM UNSW Business School 2024

- Christensen, C M, Marx, M & Stevenson, H H 2006, ‘The tools of cooperation and change’, Harvard Business Review, October, pp. 72–80.

- Cialdini, R 2001, ‘Harnessing of the science of persuasion’, Harvard Business Review, vol. October 2001, pp. 72–79.

- Cybersecurity Trends & Statistics; More Sophisticated And Persistent Threats So Far In 2023, Forbes 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckbrooks/2023/05/05/cybersecurity-trends–statistics-more-sophisticated-and-persistent-threats-so-far-in-2023/

- Hughes, M 2016, ‘Leading changes: Why transformation explanations fail’, Leadership, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 449–469.

- Johnson, G, Scholes, K & Whittington, R 2008, Exploring strategy, 8th edn, Financial Times Prentice Hall.

- Kotter, J P 2007, ‘Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 1–10.

- Kotter, J P 2012, ‘Accelerate!’, Harvard Business Review, November, p. 10.

- Kotter, J P, Akhtar, V & Gupta, G 2021, Change: How organizations achieve hard- to-imagine results despite uncertain and volatile times, Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey. Kotter, J P 2007, ‘Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 1–10.

- Yukl, G, Seifert, C F, & Chavez, C 2008, ‘Validation of the extended influence behavior questionnaire’, The Leadership Quarterly, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 609–621

3 Comments