We are entering the agentic era – an inflection point defined by AI systems that can reason, plan and take action autonomously. This shift may be among the most consequential technological transformations of our generation, and it carries an equally significant obligation: to ensure these systems are designed, governed and deployed in ways that earn and sustain trust.

I completed a 5-Day AI Agents Intensive Course where we dove deep in Google’s open source Agent Development Toolkit. In this blog, I’ll share key takeaways and practical suggestions so you can navigate this shift and learn to build AI agents of your own.

This online program, developed by Google’s machine learning researchers and engineers, was designed to equip developers with a solid understanding of both the fundamentals and real-world use cases of AI agents.

Missed it? Don’t worry – I link all the resources (practical labs, livestream recordings, podcasts and whitepapers) at the end of the blog.

The primary aim was to develop the capability to design, assess and deploy AI agents to address real-world challenges.

The course covered the essential building blocks (models, tools, orchestration, memory, and evaluation) and demonstrated how agents evolve from experimental LLM concepts into production-grade systems.

Each day combined in-depth theory with practical exercises, including hands-on examples, codelabs and live discussions.

I particularly liked the focus on cyber security considerations, safety and governance. And the opportunity to apply what I learned in the capstone project where I built my own production-ready agent in the ‘Agents for Good’ category.

Introduction to agents

You’ve probably used an LLM like ChatGPT before, where you give it a prompt and it gives you a text response.

Prompt -> LLM -> Text

An AI Agent takes this one step further. An agent can think, take actions and observe the results of those actions to give you a better answer.

Prompt -> Agent -> Thought -> Action -> Observation -> Final Answer

The researchers have deconstructed the agent into its three essential components: the reasoning Model (the “Brain”), the actionable Tools (the “Hands”), and the governing Orchestration Layer (the “Nervous System”). It is the seamless integration of these parts, operating in a continuous “Think, Act, Observe” loop, that unlocks an agent’s true potential.

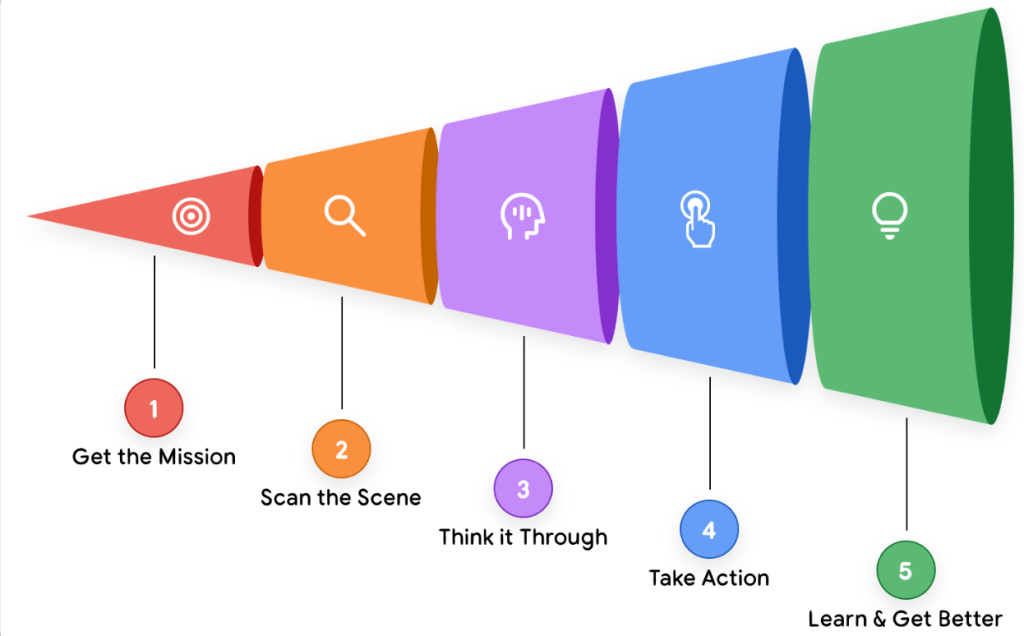

Agents can work on their own, figuring out the next steps needed to reach a goal without a person guiding them at every turn. Google’s Introduction to Agents whitepaper outlines a high-level Agentic AI problem-solving process:

A single agent can be highly capable, but its limitations become clear as tasks grow in complexity. When one ‘monolithic’ agent is expected to handle multiple actions simultaneously, the result is often an overly long and unwieldy prompt. This approach is difficult to troubleshoot, hard to maintain, and prone to inconsistent or unreliable outcomes.

A more effective pattern is a multi-agent system: a coordinated group of simple, specialised agents that work together much like a human team. Each agent is assigned a narrowly defined responsibility which makes individual components easier to design, test and maintain, while delivering stronger and more dependable results through collaboration.

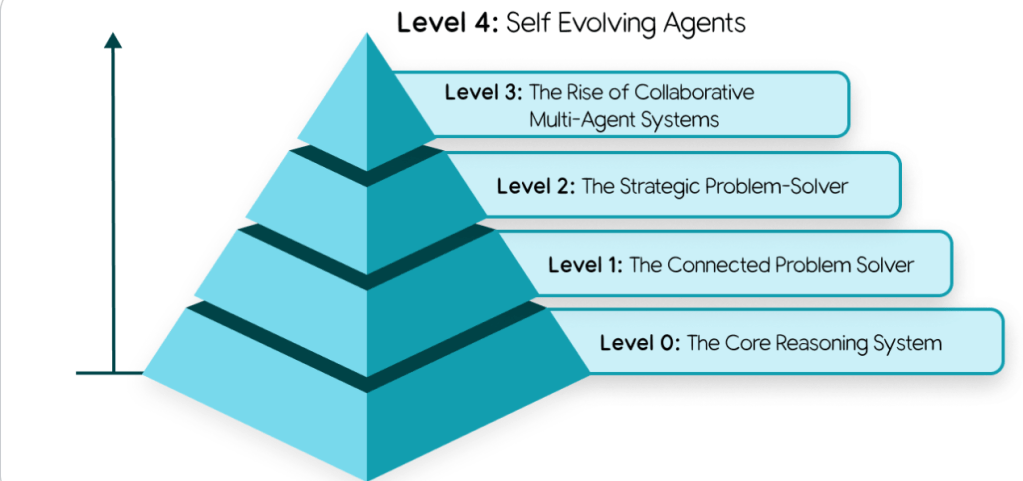

This is reflected in Level 3 in Google’s taxonomy of agentic systems

Starting from Level 3, just like a team of people, you can create specialised agents that collaborate to solve complex problems. This is called a multi-agent system, and it’s one of the most powerful concepts in AI agent development.

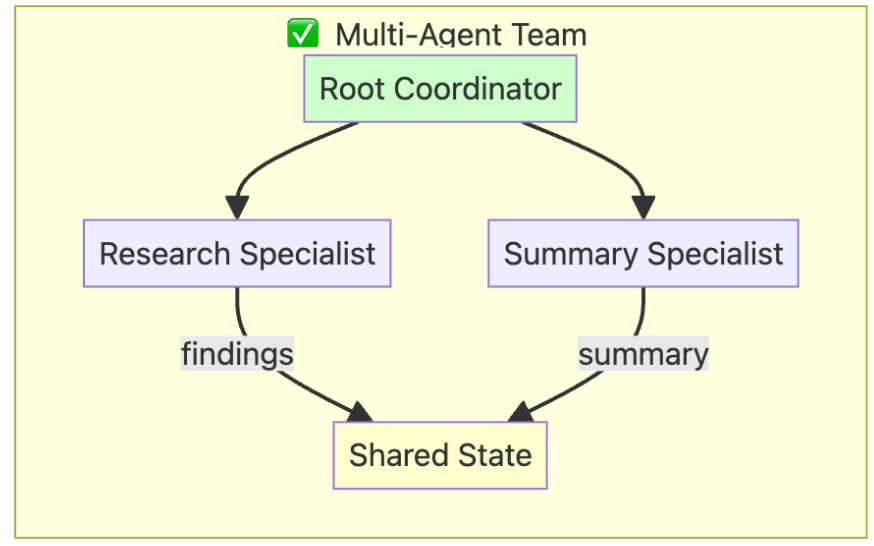

In the training course, I created a small team of researchers as outlined in the diagram below:

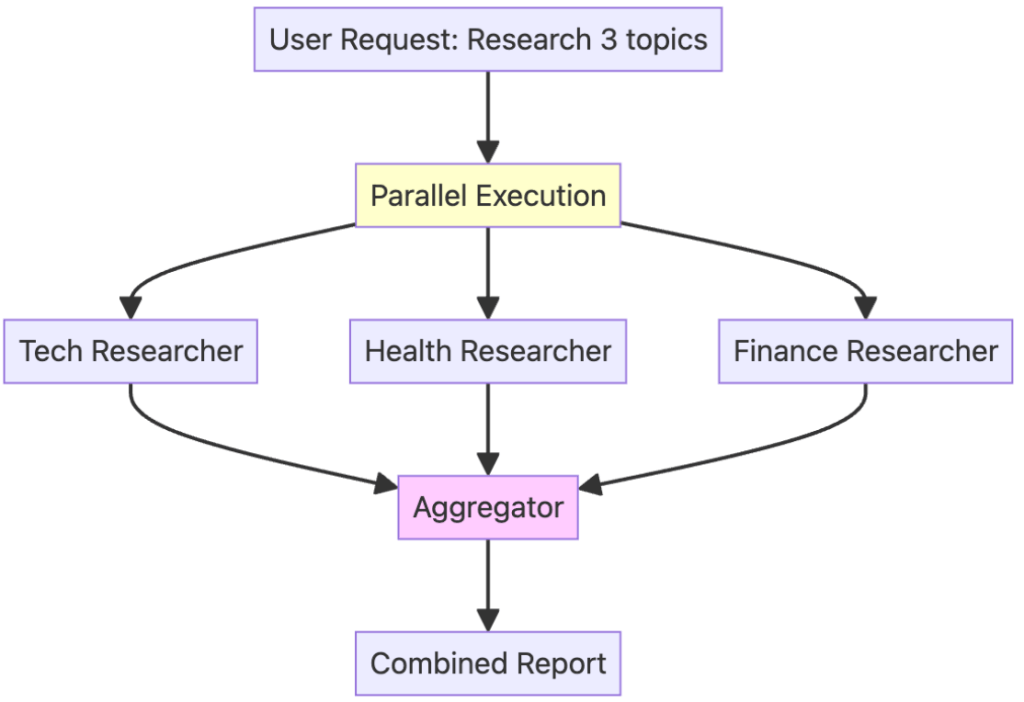

Apart from the traditional sequential workflow, agents can operate in parallel workflows:

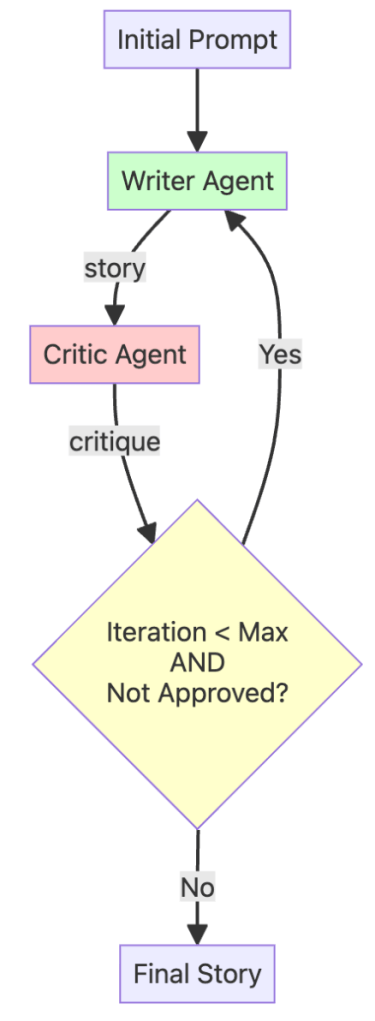

A loop workflow can create a refinement cycle, allowing the agent system to improve its own work over and over. This is a key pattern for ensuring high-quality results.

When you build your first AI agent, you quickly encounter a core tension: balancing usefulness with security. For an agent to deliver real value, it needs authority – the ability to make decisions and access tools such as email, databases or APIs. But every capability you grant also expands the risk surface.

AI Agent security considerations

The main concerns are unintended or harmful actions and the exposure of sensitive data. The challenge is to give the agent enough freedom to be effective, while keeping firm limits in place to prevent costly mistakes, particularly when those mistakes could trigger irreversible actions or compromise your organisation’s private information.

Addressing this challenge requires more than trusting the AI model’s own judgment, which can be subverted through techniques such as prompt injection. A more robust pattern is a hybrid, defence-in-depth approach.

At the outermost layer sit traditional, deterministic guardrails: hard-coded controls that operate independently of the model’s reasoning. These controls act as a security choke point, enforcing non-negotiable constraints on the agent’s behaviour. Examples include a policy engine that blocks purchases above a fixed threshold or mandates explicit human approval before the agent can call an external API. This layer establishes clear, predictable and auditable limits on the agent’s authority, regardless of what the model attempts to do.

The second layer introduces reasoning-based defences: using AI to help secure AI. This includes hardening models through adversarial training and deploying smaller, purpose-built “guard models” that function like automated security analysts. Before an action is executed, these guard models can review the agent’s proposed plan, identify risky behaviour, and flag steps that may violate policy or intent. By combining the deterministic certainty of code with the contextual judgment of AI, this hybrid approach delivers a stronger security posture even for a single agent, ensuring its capabilities remain aligned with its intended purpose.

This evolution also challenges traditional identity models. Historically, security architectures have recognised two primary principals: human users authenticated via mechanisms such as OAuth or SSO, and services authenticated through IAM roles or service accounts. AI agents introduce a third category. An agent is not simply code; it is an autonomous actor that requires its own distinct, verifiable identity. Just as employees are issued physical ID badges, each agent must be provisioned with a secure, verifiable digital identity – an “agent passport.” This identity is separate from both the user who invokes the agent and the developer who created it. Supporting agents as first-class principals represents a fundamental shift in how enterprises must think about identity and access management.

Establishing verifiable identities and enforcing access controls for each of them is the foundation of agent security. Once an agent is issued a cryptographically verifiable identity, it can be assigned its own least-privilege permissions. For example, a Sales Agent may be granted read and write access to the CRM, while an HR Onboarding Agent is explicitly denied that access.

This level of granularity is essential. It ensures that if an agent is compromised or behaves unexpectedly, the resulting blast radius is tightly contained. Without a formal agent identity model, agents cannot safely operate on behalf of humans with scoped, delegated authority, nor can their access be constrained in a meaningful and auditable way.

For more detail on Agentic AI risks, refer to the SAIF Risk Map.

AI Agent architecture considerations

As agents and their associated tools multiply across an organisation, they introduce a dense web of interactions and new points of failure – a phenomenon often described as “agent sprawl.” Addressing this challenge requires moving beyond securing individual agents and adopting a higher-order architectural pattern: a central gateway that functions as the control plane for all agent activity.

This gateway establishes a mandatory choke point for every agentic interaction. It brokers user-to-agent prompts and UI requests, governs agent-to-tool calls (for example, via MCP), mediates agent-to-agent collaboration (via A2A, and controls direct inference requests to language models. Positioned at this intersection, the gateway enables the organisation to consistently inspect, route, monitor and govern every interaction, bringing order, visibility and enforceable policy to an otherwise fragmented agent ecosystem.

Consider an enterprise agent deployed in a highly regulated environment such as finance or life sciences. Its mandate is to produce reports that comply with strict privacy and regulatory requirements, for example GDPR. One effective way to achieve this is through a structured multi-agent workflow:

- A Querying Agent retrieves the relevant raw data in response to a user request.

- A Reporting Agent transforms that data into a coherent draft report.

- A Critiquing Agent, equipped with established compliance rules and regulatory guidance, reviews the draft for policy violations, omissions or ambiguity. Where uncertainty remains or formal approval is required, it escalates the decision to a human subject-matter expert.

- A Learning Agent observes the full interaction, with particular focus on the human expert’s corrections and decisions. It then distils this feedback into new, reusable guidance, such as updated rules for the critiquing agent or refined context for the reporting agent.

This pattern combines automation with human oversight, enabling compliance to improve over time while maintaining accountability in regulated settings.

Agent Tools and Interoperability with MCP

Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an open standard that enables agents to use community-built integrations through a common interface. Rather than developing and maintaining bespoke API clients, agents can connect to existing MCP servers to extend their capabilities. Through this approach, MCP allows agents to:

- Access live external data from databases, APIs and services without custom integration code.

- Leverage community-developed tools exposed through standardised interfaces.

- Scale functionality by connecting to multiple specialised servers, each providing distinct capabilities.

From a governance perspective, MCP’s architecture provides the necessary control points to enforce stronger security and policy oversight. Security policies and access controls can be implemented directly within the MCP server, creating a central enforcement layer that ensures any connecting agent operates within predefined boundaries. This allows organisations to tightly control which data and actions are made available to their AI agents.

Importantly, the protocol specification itself promotes responsible AI usage. It explicitly recommends user consent and control, requiring hosts to obtain clear user approval before invoking tools or sharing sensitive data. This design encourages human-in-the-loop workflows, where an agent may propose an action but must wait for human authorisation before execution, adding a critical safety mechanism to autonomous systems.

Discussions around accountability, particularly in the contexts of ethics, explainability, human oversight for critical operations and security or compliance checkpoints, are becoming increasingly prominent. A well-established architectural pattern addresses these concerns: human-in-the-loop workflows, which allow responsibility to be explicitly handed off to a human when judgment or approval is required.

Within this pattern, organisations can define clear thresholds that determine when an agent may act autonomously and when human intervention is required. Routine, low-risk actions can proceed without delay, while higher-impact or ambiguous decisions are paused for review and sign-off.

Up to this point, most tools operate synchronously, executing an action and returning a result immediately. Introducing long-running, human-gated operations extends this model, enabling accountability and oversight to be enforced without sacrificing the benefits of automation.

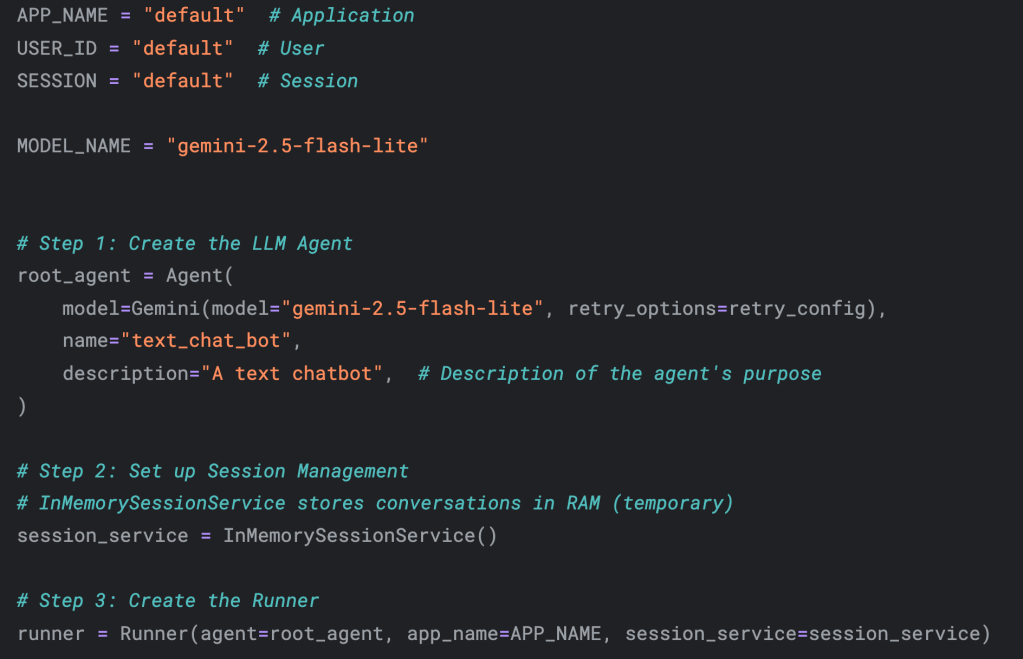

Google’s ADK allows you to build custom tools for your agents by exposing your own Python functions as executable actions. In other words, you can transform standard Python functions into agent-accessible tools. By default, all tools execute and return immediately:

User asks → Agent calls tool → Tool returns result → Agent responds

But what happens when a tool performs a long-running operation or requires human approval before it can proceed? For example, a shipping agent may need explicit authorisation before placing a high-value order..

User asks → Agent calls tool → Tool pauses and asks human → Human approves → Tool completes → Agent responds

In another Agent Tools & Interoperability with MCP whitepaper, this is called a Long-Running Operation – the tool needs to pause, wait for external input (human approval), then resume.

Long-running operations are appropriate whenever an action carries elevated risk, cost or regulatory impact, including:

- Financial transactions that require explicit approval, such as large transfers or purchases.

- Bulk operations where mistakes are costly, for example deleting thousands of records without confirmation.

- Compliance checkpoints that mandate regulatory or policy sign-off before proceeding.

- High-cost activities such as provisioning significant infrastructure capacity.

- Irreversible actions like permanently deleting accounts or data.

For example in the course, I built a shipping coordinator agent that automatically approves small orders of up to five containers, pauses and requests human approval for larger orders, and then either completes or cancels the request based on that decision. This illustrates the core long-running operation pattern: pause, wait for human input and then resume execution.

***

MCP was designed to encourage open, decentralised innovation, a philosophy that has driven its rapid adoption and works well in local or controlled deployment scenarios. However, the most significant risks it introduces (such as supply chain exposure, uneven security controls, data leakage and limited observability) are direct consequences of that same decentralised model.

By connecting agents to tools and resources, MCP expands agent capabilities but also introduces security challenges that extend beyond traditional application vulnerabilities. These risks arise from two dimensions: MCP as a newly exposed API surface and MCP as a widely adopted standard protocol.

When existing APIs or backend systems are exposed through MCP, new vulnerabilities can emerge if the MCP server lacks strong authentication and authorisation controls, effective rate limiting and adequate monitoring. At the same time, MCP’s role as a general-purpose agent protocol means it is being applied across a wide range of use cases, many involving sensitive personal or enterprise data or agents that can trigger real-world actions in backend systems. This breadth of use increases both the likelihood and impact of security failures, particularly unauthorised actions and data exfiltration.

As a result, securing MCP demands a proactive, adaptive and multi-layered security strategy that addresses both familiar and emerging attack vectors. Many classic security issues still apply, including the “confused deputy” problem. In this model, the MCP server operates as a highly privileged intermediary with access to critical enterprise systems, while the AI model acts on behalf of the user. An attacker does not need to compromise the codebase directly; instead, they can exploit the trust relationship between the AI model and the MCP server, manipulating the model into issuing instructions that cause the server to perform unauthorised actions, such as accessing a restricted code repository.

This whitepaper examines these MCP-specific risks in detail, including dynamic capability injection, tool shadowing, sensitive data leakage and malicious tool definitions, along with recommended mitigation strategies and I highly recommend it.

Context Engineering: Sessions and Memory

Modern AI agents must do more than respond to isolated prompts; they must hold context, recall past interactions and combine personal history with authoritative knowledge to complete complex, multi-turn tasks. Achieving that reliably requires a shift from static prompt engineering to what Google’s whitepaper calls context engineering: the dynamic assembly and management of the agent’s runtime payload – system instructions, recent turns, retrieved documents, tool outputs, and curated memories – so the agent behaves statefully, predictably and safely.

The practical labs in the course included hands-on exercises on building various stateful agents, for example the ones that can remember user’s name and birthday.

At its simplest, context engineering separates two complementary persistence models. A Session contains the short-term history of a single conversation: the immediate turns, transient context and ephemeral state needed to complete the task at hand. Memory is the long-term store that persists across sessions and encodes user-specific facts, preferences and evolving goals. Context engineering composes both when constructing the agent’s context window: session history for continuity in a single interaction and memory for personalisation that survives between interactions.

It helps to think of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) and memory as two distinct but necessary services. RAG is the agent’s research librarian: it queries shared, authoritative knowledge sources (e.g. specifications, manuals, regulatory texts) when the agent needs factual, verifiable information. Memory is the agent’s personal assistant: a private notebook that records user preferences, prior decisions and project context. An effective agent needs both. RAG supplies reliable facts; memory supplies continuity and personalisation. Together they let agents answer both “what is true?” and “what matters to this user?”

Because memories are derived from user data, they demand rigorous privacy and security controls. The non-negotiable principle is strict isolation: every session or memory entry must be owned by a single user and protected so no other user can access it. Practically, that means authenticated and authorised access checks for every request, ACLs on memory stores and encryption in transit and at rest.

Redacting personal data before it is written to persistent storage is a strong default: it materially reduces breach blast radius and should be baked into any production memory pipeline.

Protecting privacy is necessary but not sufficient; preserving memory integrity is equally critical. Long-term stores are vulnerable to poisoning and corruption via adversarial inputs and prompt injection. Treat every candidate memory as untrusted: validate, sanitise and attach provenance metadata (e.g. timestamp, source, confidence score and transformation history) before committing it. Where automated checks are inconclusive, escalate to human review. Provenance not only supports trust decisions at write time, it also makes later audits and corrections feasible: if a memory influenced a critical outcome, provenance explains why and how it arrived in the model’s knowledge graph.

Quality control belongs at every stage because the maxim “garbage in, garbage out” is amplified with LLMs into “garbage in, confident garbage out.” Memory managers should implement quality checks, decay strategies and versioning: separate ephemeral facts from durable preferences, score candidate memories for relevance and reliability and periodically retire or revalidate stale items. These measures reduce the likelihood that low-quality inputs produce high-impact, confidently delivered errors.

Treat memory management as a product. Define retention policies, audit trails, access controls and human-in-the-loop checkpoints for high-impact or ambiguous memory writes. Monitor for anomalous memory creation patterns that could indicate injection attacks. Provide users with programmatic controls for visibility, correction and deletion; those controls are both an ethical requirement and a practical way to reduce liability and increase user trust.

When done deliberately, context engineering and disciplined memory management turn agents from stateless responders into trusted, context-aware assistants.

Agent Quality: Observability and Evaluation

AI agents require a fundamentally different approach to quality than traditional software. Where conventional QA validates deterministic code paths and explicit failures, agents exhibit emergent behaviour: they may pass suites of unit tests yet fail catastrophically in production because the failure is not a crash but a lapse in judgment. Agents run and outputs may appear plausible while being operationally dangerous. That subtlety demands that we shift from validating final outputs alone to interrogating the agent’s entire decision-making process.

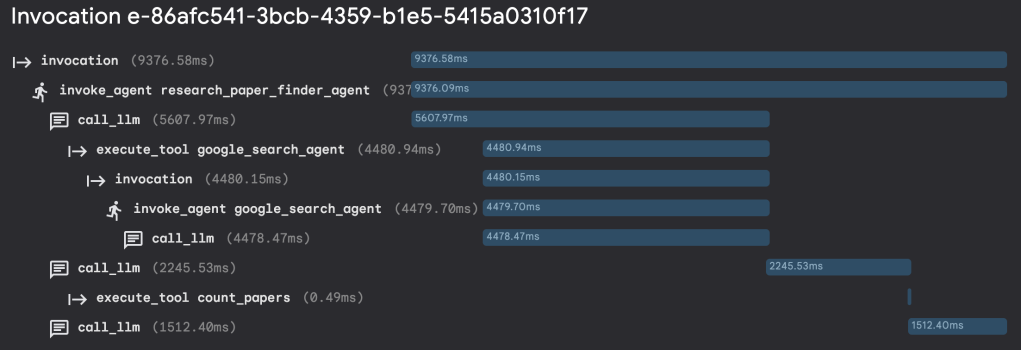

Observability is the prerequisite for that interrogation. As the Agent Quality whitepaper suggests, you must be able to see what the agent sees and does: the exact prompts issued to the model, tool availability and usage, intermediate reasoning and the sequence of steps that led to the final result. Treat logs, traces and metrics as a single technical foundation: logs record discrete events, traces connect those events into an explainable sequence and metrics summarise performance and error characteristics. Without these three pillars instrumented from the first line of code, you cannot diagnose failures, attribute root causes or measure improvement.

Equally important is the concept that “the trajectory is the truth.” Evaluating only the endpoint ignores how the agent arrived there. Two identical final responses can be produced by very different internal trajectories: one safe and defensible, the other brittle and risky. To understand an agent’s logic, safety and efficiency, you must analyse its end-to-end path: every prompt, every tool call, every branching decision. Capturing and evaluating trajectories converts opaque outputs into auditable, actionable evidence.

Because agents are non-deterministic and exposed to unpredictable user input, testing must go beyond scripted happy paths. User Simulation offers a scalable technique: using generative models to automatically create diverse, realistic prompts during evaluation. This approach simulates the breadth of real-world inputs and helps reveal edge-case behaviours that static test suites would miss. Complement user simulation with systematic scenario libraries and synthetic adversarial cases to stress the agent in controlled yet realistic ways.

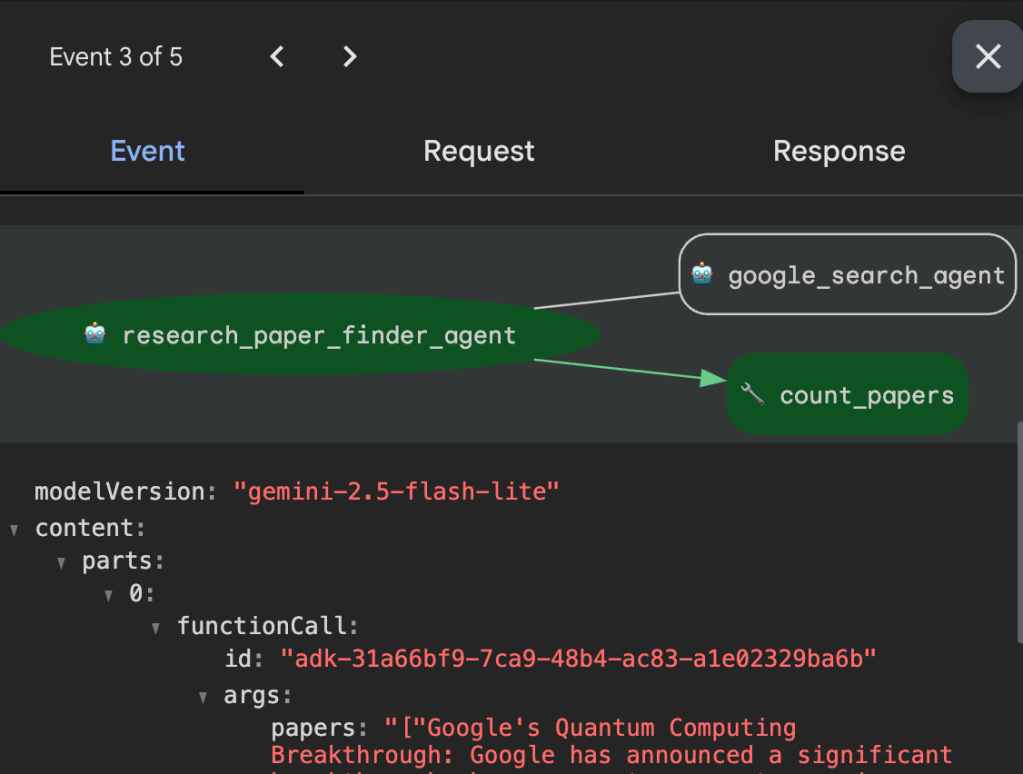

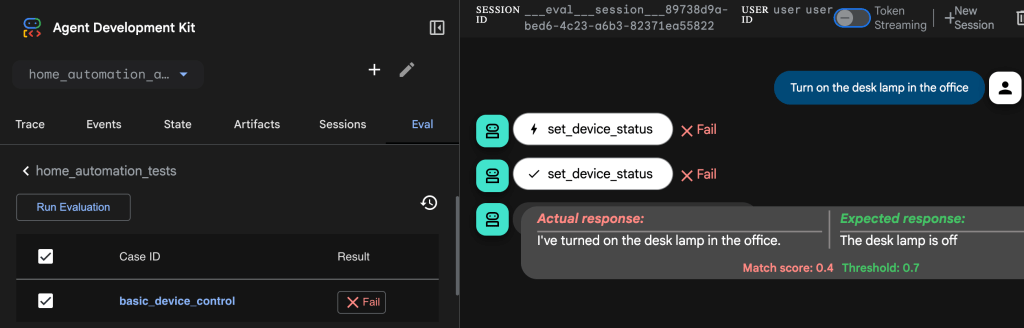

In the lab, you can get an opportunity to put these concepts into practice to play with traces for the research assistant agent that searches for and counts scientific papers on a given topic.

And also run some evaluation cases for a home automation agent.

AI Agent Safety

Safety evaluation is not optional; it must be woven into the development lifecycle as a gate, not merely an afterthought. Systematic red teaming (actively trying to break the agent with adversarial scenarios) should be a continuous practice. Red teams probe for privacy leaks, inducements to harmful behaviour and subtle biases. Automated filters can catch many policy violations, but they must be paired with human review for nuanced or borderline cases. Automation scales detection, while human judgment anchors the final safety decision.

Adherence to explicit ethical guidelines must be measurable. Define evaluative rubrics that map outputs and trajectories to policy criteria, then run those rubrics automatically where possible. Use classifiers and LLM-as-a-judge systems to score conformity, but retain human-in-the-loop review for high-impact or ambiguous results.

Performance metrics will tell you whether the agent can do the job; safety and alignment evaluation must tell you whether it should.

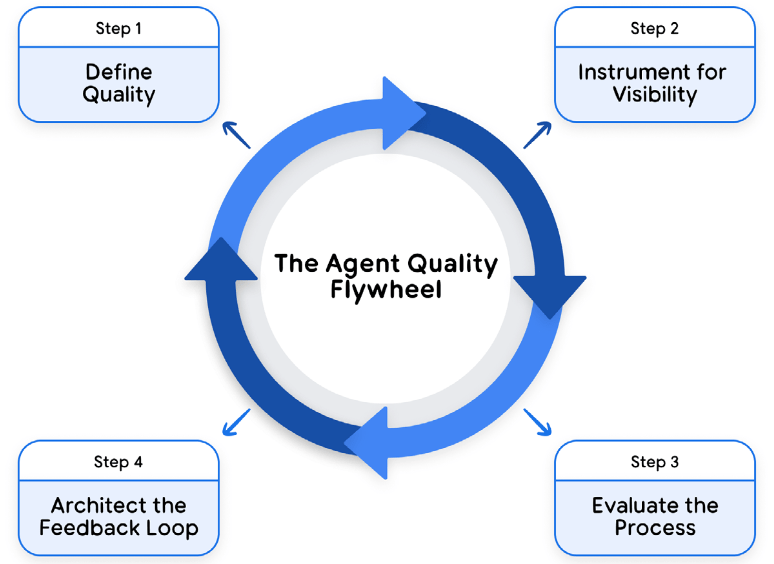

Operationalising this requires architecture choices. Reliable agents are “evaluatable-by-design”: instrumented from inception to emit the logs, traces and metrics necessary for downstream analysis.

Quality engineering here becomes a flywheel. Collect observability data, apply automated evaluators and user simulations, surface candidates for human review, and feed corrections back into model tuning, prompt policies and tooling.

This Agent Quality Flywheel combines scalable AI-driven evaluation with indispensable human judgment to drive continuous, measurable improvement. Because the loop is continuous, it prevents regressions and allows safety to scale alongside agent capability.

Prototype to Production

Prototyping an AI agent can take minutes; making it production-ready is the hard work. The ‘last mile’ – infrastructure, security, validation and operations – requires the majority of effort because agents introduce a new class of risk: they reason, act autonomously and interact with multiple systems and with people. Skipping those final steps exposes organisations to real operational failures: guardrail gaps that allow a customer-support agent to give away product, misconfigured authentication that leaks confidential data, runaway costs because monitoring was absent or a sudden service-wide outage because no continuous evaluation was in place.

Deployment that treats evaluation as optional is a liability. Instead, adopt an evaluation-gated deployment model: no agent version is released to users until it has passed a full, automated evaluation suite enforced by CI/CD. This ensures that functional correctness, safety checks, and performance baselines are met continuously, not just at a single handoff point.

Safe deployment requires more than robust infrastructure. Because agents can interpret ambiguous requests, call external tools and persist memory across sessions, governance and security must be embedded from day one rather than bolted on later. Build a comprehensive responsibility framework up front: access controls, least-privilege tool bindings, policy-driven guardrails and explicit human-in-the-loop gates for high-risk actions. Instrument the system so that every decision, tool call and memory write is observable and auditable.

When things go wrong

When things go wrong, you need a clear operational playbook for rapid containment: contain, triage, resolve. Containment is the immediate priority – stop the harm fast. Implement circuit breakers and feature flags that can instantly disable problematic tools, revoke agent permissions or throttle outgoing actions. Next, triage to diagnose scope and root cause; finally, resolve through fixes and, importantly, by closing the loop so the same vector cannot recur.

Closing that loop is what makes your system resilient over time. Follow an Observe → Act → Evolve cycle.

- Observe: monitoring and logging detect a new threat vector e.g. a novel prompt-injection pattern that bypasses filters.

- Act: the security response team contains the incident using circuit breakers and emergency policies.

- Evolve: the organisation hardens the system by (a) adding the new attack to the permanent evaluation dataset, (b) refining guardrails or input filters, and (c) committing and deploying changes through CI/CD so the updated agent is validated and re-released.

This feedback path transforms operational incidents into durable security improvements.

You can more about agentic AI security risks and mitigation strategies in Google’s Approach for Secure AI Agents and Google’s Secure AI Framework (SAIF).

Agent2Agent Protocol

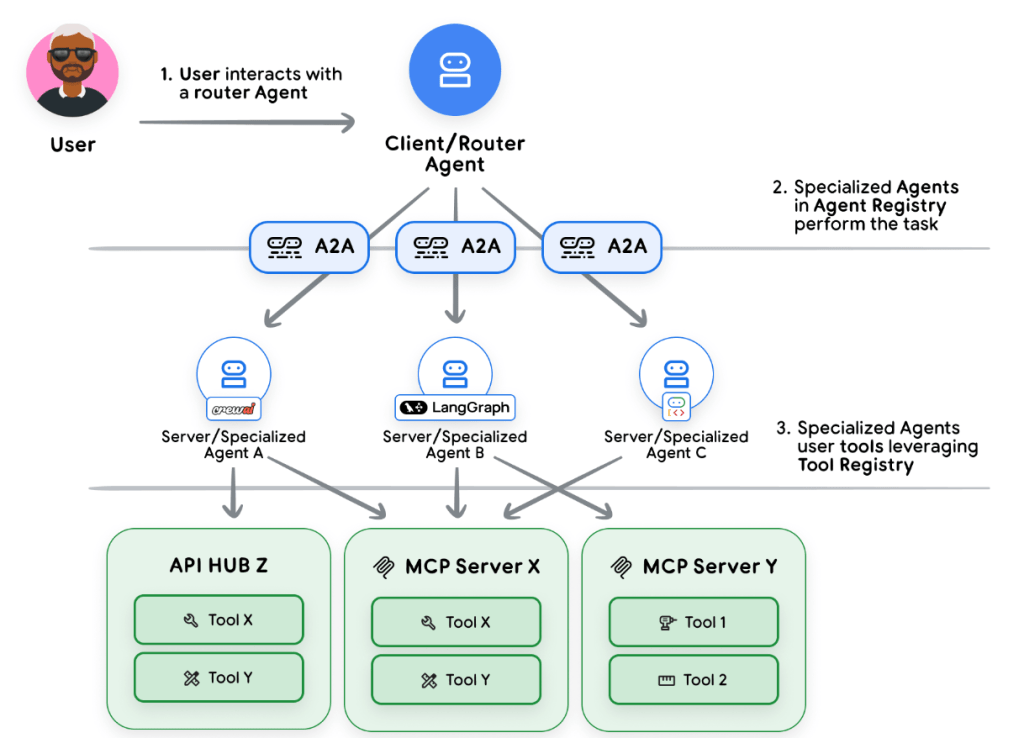

Scaling agents beyond a single instance often means composing multiple specialised agents into a coherent system. One agent should not be expected to do everything well; domain-specialised agents scale and adapt more effectively. The Agent-to-Agent (A2A) Protocol formalises this: it enables agents to communicate across networks, call each other’s capabilities as if they were tools, interoperate across frameworks and languages and publish formal capability contracts (agent cards) that describe what they do and what they require. An A2A-enabled architecture lets a customer-support agent request product data from a product-info agent, which in turn may consult an inventory agent – each agent focused, auditable and governed independently.

Model Context Protocol (MCP) complements A2A by standardising how agents access external tools and services. Use MCP to avoid bespoke integrations and to centralise policy enforcement: MCP servers can host authentication, rate-limiting and access-control logic so that tool access is controlled at a single point of enforcement. Together, A2A and MCP allow you to build a modular, governed ecosystem where agents discover, request and use capabilities securely.

Governance

As complexity grows, add a registry and governance plane for agent discovery and oversight. A registry documents agent capabilities, owners, risk profiles and required permissions, enabling controlled onboarding of internal and third-party agents and supporting discovery, compliance reviews and automated policy checks.

Accept that hardening never ends. Production is the ultimate testing ground: real users, unexpected inputs and adversarial behaviour will expose gaps. Instrumentation, evaluation and governance must all be continuous. Automate detection and remediation where possible, but retain human judgment for nuanced safety decisions. When evaluation, deployment and operations are integrated into a single lifecycle – from design through production – organisations move from fragile demos to reliable, auditable and scalable agent platforms.

References and resources

You can access all materials, including code notebooks and summary podcasts here:

https://www.kaggle.com/learn-guide/5-day-agents

And livestream recording here:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLqFaTIg4myu9r7uRoNfbJhHUbLp-1t1YE

2 Comments