My publisher kindly made one of the chapters of my audiobook available for free. In it, I discuss the role of uncertainty in making decisions and managing risk.

Agile security. Part 2: User stories

In the previous blog, I wrote about how you as a security specialist can succeed in the world of agile development, where the requirements are less clear, environment more fluid and change is celebrated not resisted.

Adjusting your mindset and embracing the fact that there will be plenty of unknowns is the first step in adopting agile security practices. You can still influence the direction of the product development to make it more resilient, safe and secure by working with the Product Owner and contributing your requirements to the product backlog.

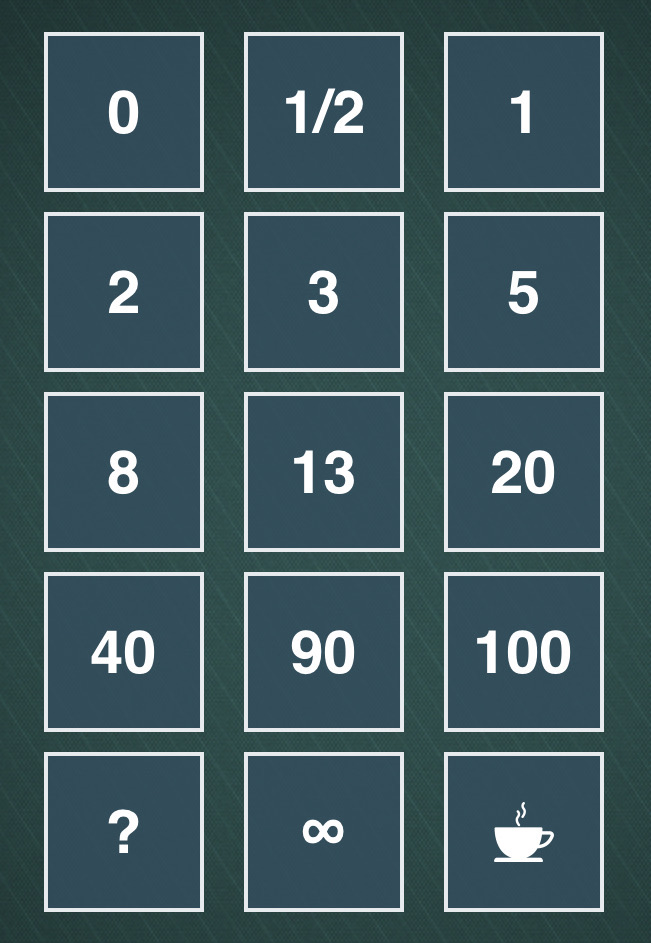

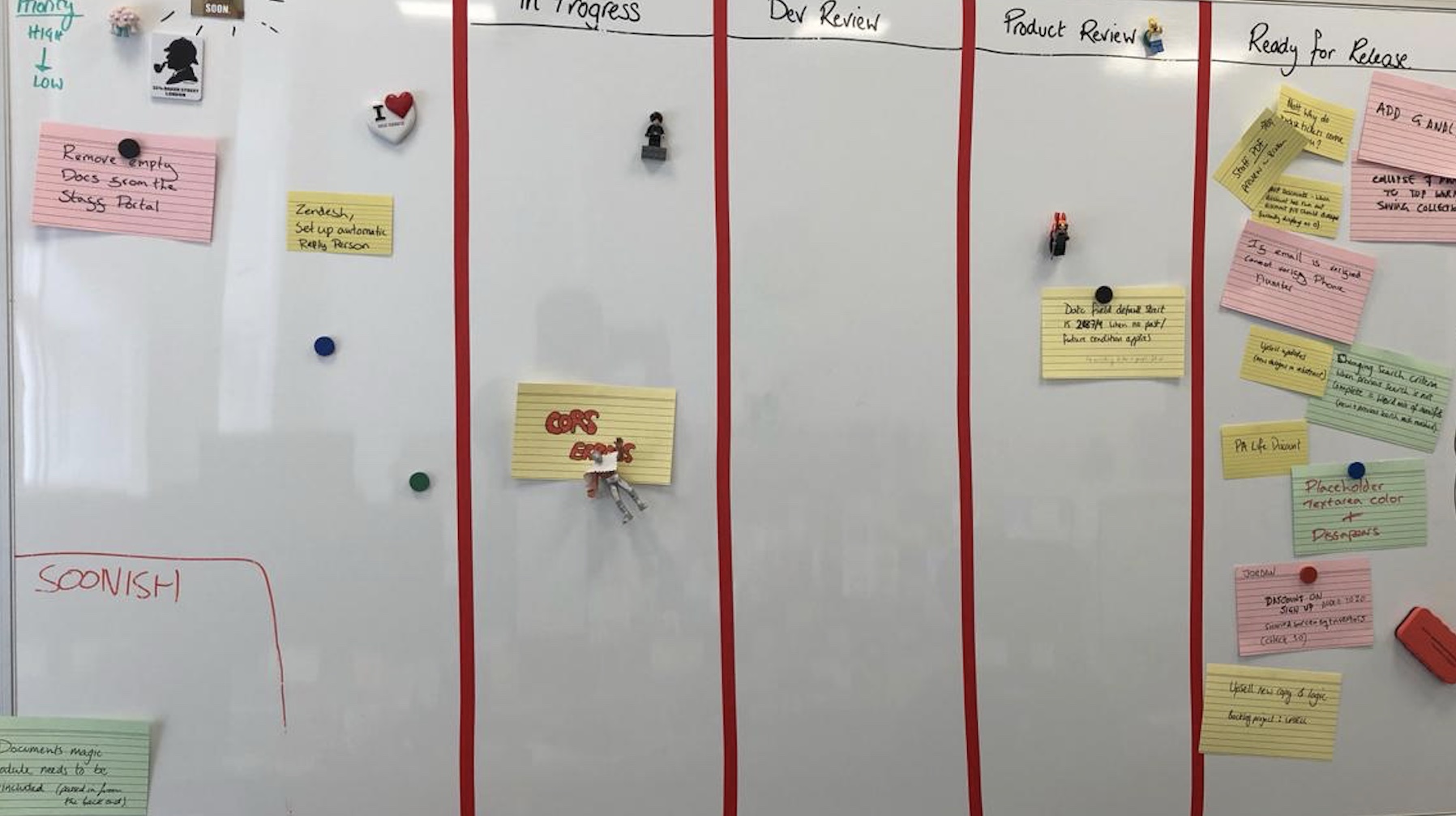

Simply put, product backlog is a list of desired functionality, bug fixes and other requirements needed to deliver a viable product. There are plethora of tools out there to help manage dependencies and prioritisation to make the product owner’s job easier. The image at the top of this post is an example of one of such tools and you can see some example requirements there.

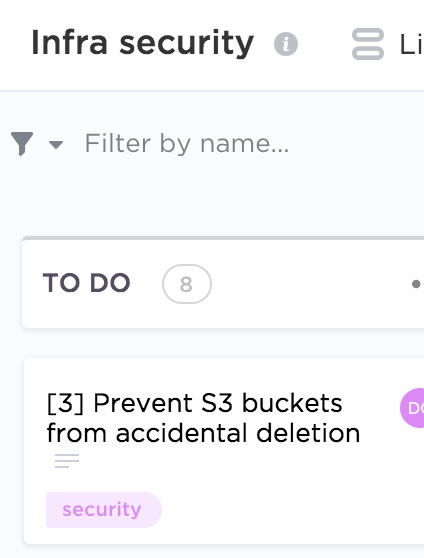

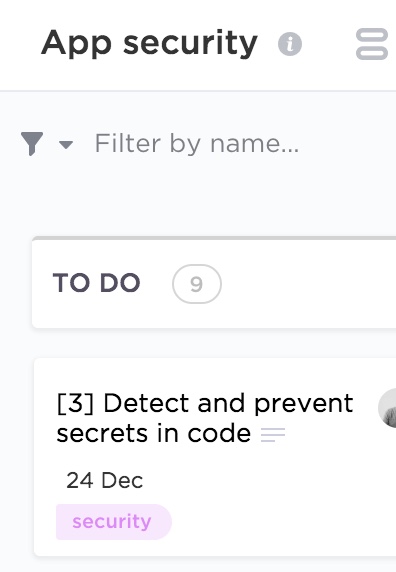

As a security specialist, you can communicate your needs in a form of user stories or help contribute to existing ones, detailing security considerations. For example, ”Customer personal data should be stored securely” or “Secure communication channels should be used when transmitting sensitive information”. Below are a couple more examples from different categories.

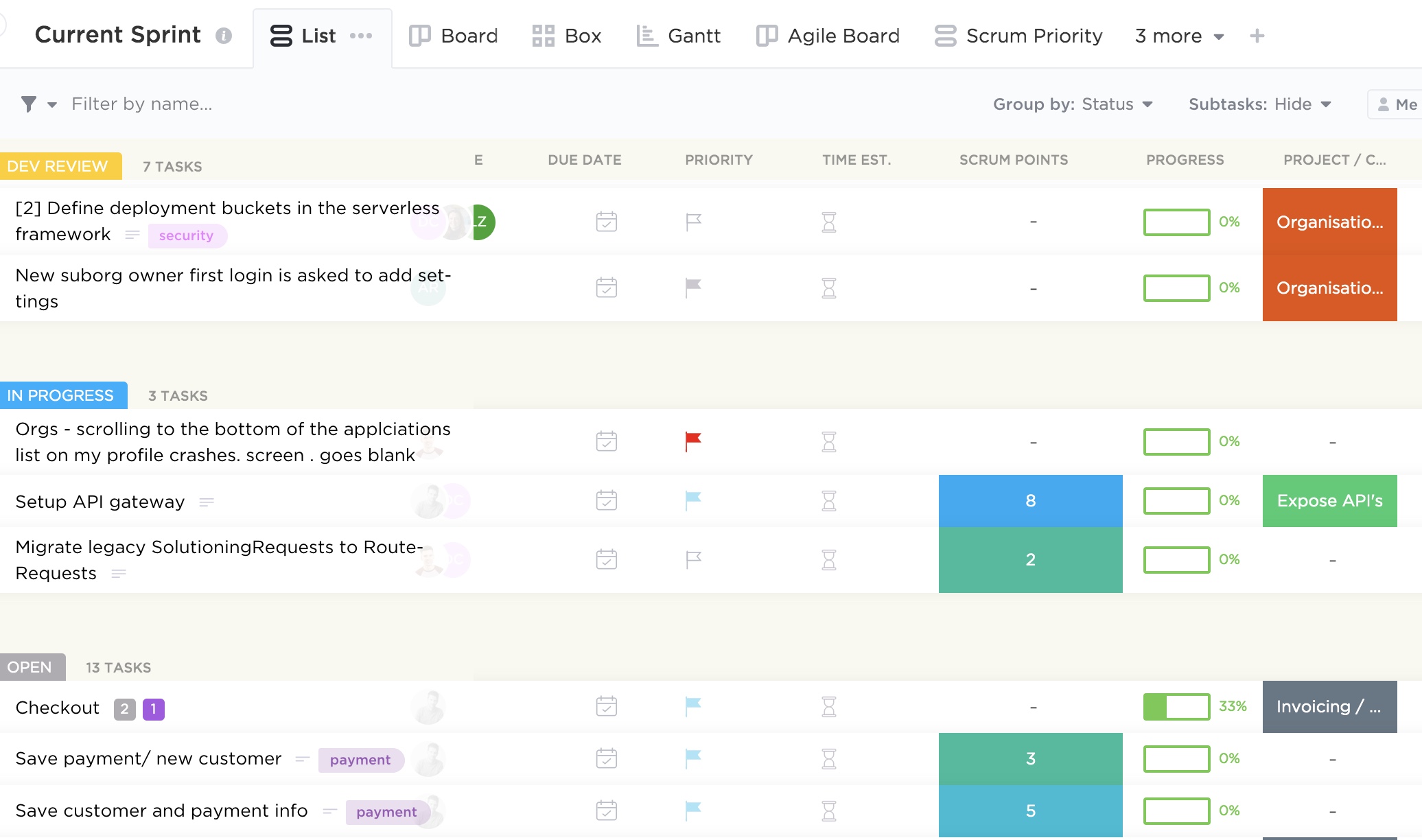

When writing security user stories, you should try and elaborate as much as possible on the problem you are trying to solve, what value it will provide if solved and the acceptance criteria. Each story will then have points assigned which signifies how much effort a particular functionality will require. The process of arriving to the final number is quite democratic and usually involves playing planning (sometimes also called Scrum) poker in which every developer will estimate how long each story is going to take with some discussion and eventual consensus. You can do it with an app as on the image below, or the old school way with a deck of cards.

You don’t have to use the above number pattern, and opt-in instead for the Fibonacci sequence or T-shirt sizes.

It’s important that the security team is involved in sprint planning to contribute to the estimates and help the product owner with prioritisation. Other Scrum meetings, like backlog refinement and daily stand-ups are also worthwhile to attend to be able clarify your requirements (including value, risk, due dates and dependencies) and help remove security related impediments.

A culture of collaboration between teams is essential for the DevSecOps approach to be effective. Treating security as not something to workaround but as a value adding product feature is the mindset product and engineering teams should adopt. However, it’s up to security specialists to recognise the wider context in which they operate and accept the fact that security is just one of the requirements the team needs to consider. If the business can’t generate revenue because crucial features that customers demand are missing, it’s little consolation that security vulnerabilities have been addressed. After all, it’s great to have a secure product, but less so when nobody uses it.

Agile security. Part 1: Embedding security in your product

Outline security requirements at the beginning of the project, review the design to check if the requirements have been incorporated and perform security testing before go-live. If this sounds familiar, it should. Many companies manage their projects using the waterfall method, where predefined ‘gates’ have to be cleared before the initiative can move forward. The decision can be made at certain checkpoints to not proceed further, accepting the sunk costs if benefits now seem unlikely to be realised.

This approach works really well in structured environments with clear objectives and limited uncertainty and I saw great things being delivered using this method in my career. There are many positives from the security point of view too: the security team gets involved as they would normally have to provide their sign-off at certain stage gates, so it’s in the project manager’s interest to engage them early to avoid delays down the line. Additionally, the security team’s output and methodology are often well defined, so there are no surprises from both sides and it’s easier to scale.

If overall requirements are less clear, however, or you are constantly iterating to learn more about your stakeholder’s needs to progressively elaborate on the requirements, to validate and perhaps even pivot from the initial hypothesis, more agile project management methodologies are more suitable.

Embedding security in the agile development is less established and there is more than one way of doing it.

When discussing security in startups and other companies adopting agile approaches, I see a lot of focus on automating security tests and educating developers on secure software development. Although these initiatives have their merits, it’s not the whole story.

Security professionals need to have the bigger picture in mind and work with product teams to not only prevent vulnerabilities in code, but influence the overall product strategy, striving towards security and privacy by design.

Adding security features and reviewing and refining existing requirements to make the product more secure is a step in the right direction. To do this effectively, developing a relationship with the development and product teams is paramount. The product owner especially should be your best friend, as you often have to persuade them to include your security requirements and user stories in sprints. Remember, as a security specialist, you are only one of the stakeholders they have to manage and there might be a lot of competing requirements. Besides, there is a limited amount of functionality the development can deliver each sprint, so articulating the value and importance of your suggestions becomes an essential skill.

Few people notice security until it’s missing, then the only thing you can notice is the absence of it. We see this time and time again when organisations of various sizes are grappling with data breaches and security incidents. It’s your job to articulate the importance of prioritising security requirements early in the project to mitigate the potential rework and negative impact in the future.

One way of doing this is by refining existing user stories by adding security elements to them, creating dedicated security stories, or just adding security requirements to the product backlog. Although the specifics will depend on your organisation’s way of working, I will discuss some examples in my next blog.

[Podcast] Interview about The Psychology of Information Security

I’ve had a chance to discuss current challenges in and approaches for building a security culture during an interview with IT Governance Publishing about my book. I also talked about why I do what I do. I hope you enjoy it.

How to manage vulnerabilities in your open source packages. Part 2: Integrating Snyk in your CI/CD pipeline

We learnt how to detect vulnerable packages in your projects using Snyk in the previous blog. Here, in the true DevSecOps fashion, I would like outline how to integrate this tool in your CI/CD pipeline.

Although the approach described in the previous blog has its merits, it lacks proactivity, which means you might end up introducing outdated packages in your codebase. To address this limitation, I’m going to describe how to make Snyk checks part of your deployment workflow. I’ll be using CircleCI here as an example, but the principles can be applied using any CI tool.

A step-by-step guidance on configuring the integration is available on both the Snyk and CircleCI websites. In the nutshell, it’s just about adding the Snyk Orb and API to CircleCI.

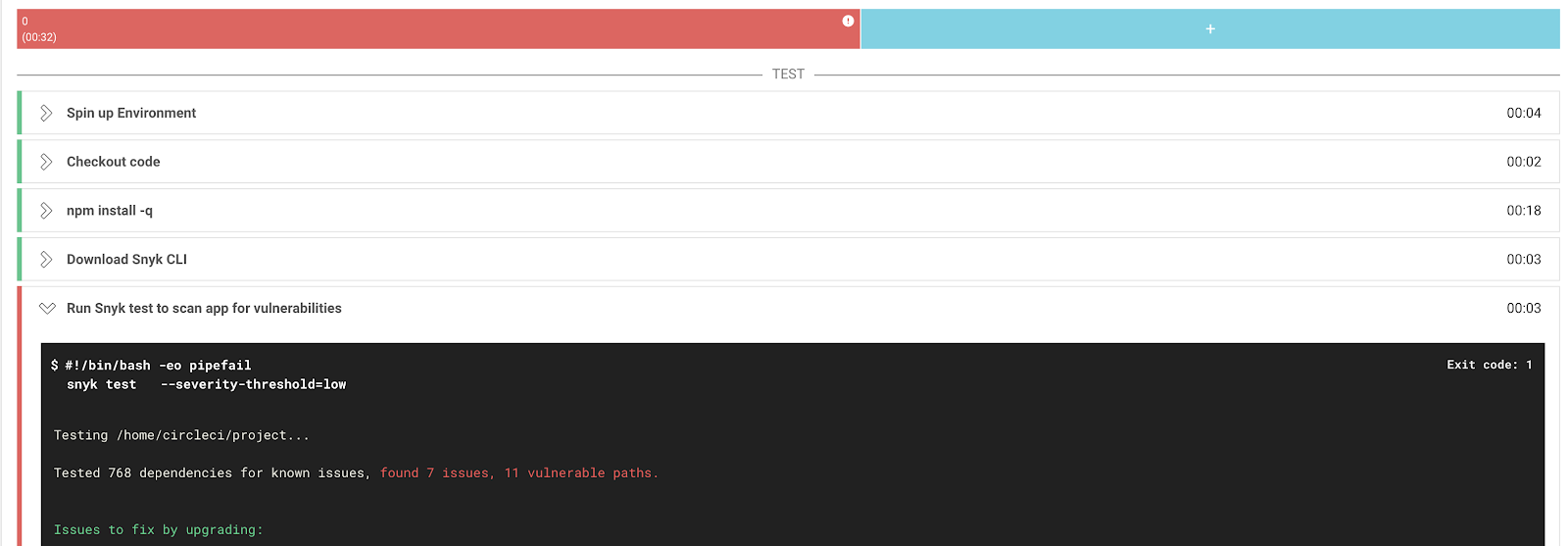

After the initial set-up, an additional test will be added to your CircleCI workflow.

If vulnerabilities are identified, you can set CircleCI to either fail the build to prevent outdated libraries to be introduced or let the build complete and flag.

Both methods have their pros and cons and will depend on the nature of your environment and risk appetite. It’s tempting to force the build fail to prevent more vulnerable dependencies being introduced but I suggest doing so only after checking with your developers and remediating existing issues in your repositories using the method described in the previous blog.

Snyk’s free version allows you only a limited number of scans per month, so you need to also weigh costs agains benefits when deploying this tool in your development, staging and production environments.

This approach will allow you to automate security tests in a developer-friendly fashion and hopefully bring development and security teams closer together, so the DevSecOps can be practiced.

How to manage vulnerabilities in your open source packages. Part 1: Using Snyk

We rely on open source libraries when we write code because it saves a lot of time (modern applications rely on hundreds of them), but these dependencies can also introduce vulnerabilities that are tricky to manage and easy to exploit by attackers.

One way of addressing this challenge is to check the open source packages you use for known vulnerabilities.

In this blog I would like to discuss how to do this using an open source tool called Snyk.

The first thing you want to do after creating an account is to integrate Snyk with your development environment. It supports a fair amount of systems, but here I would like to talk about GitHub as an example. The process of getting the rest of the integrations are pretty similar.

Snyk’s browser version has an intuitive interface and all you need to do is go to the Integrations tab, select GitHub and follow the instructions.

After granting the necessary permissions and selecting the code repositories you want tested (don’t forget the private ones too), they will be immediately scanned.

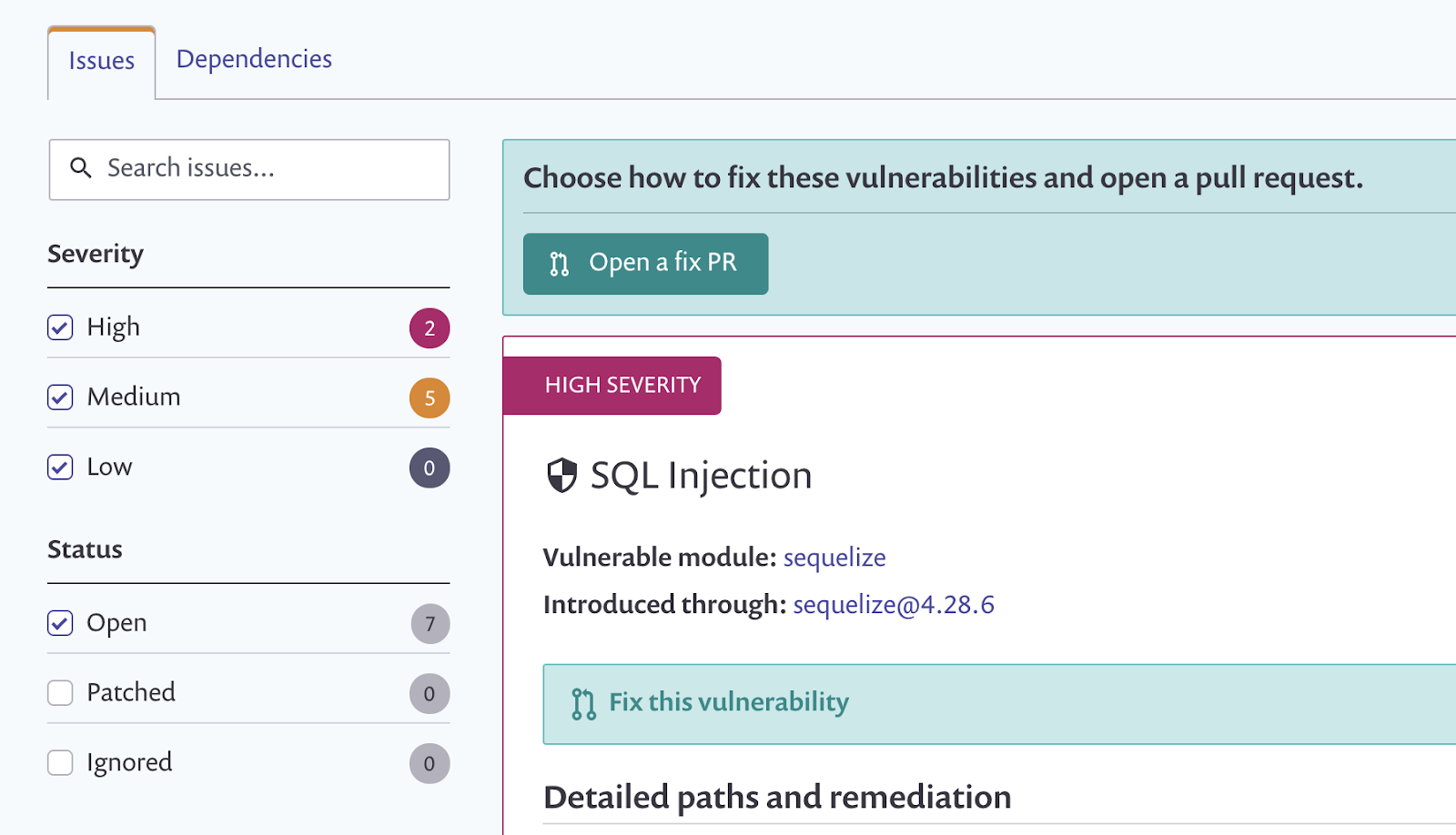

You will be able to see the results in the Projects tab with issues conveniently ordered by severity so you can easily prioritise what to tackle first. You can also see the dependency tree there which can be quite handy.

A detailed description of the vulnerability and some recommendations on how to remediate it are also provided.

Most vulnerabilities can be fixed through either an upgrade or a patch and that’s what you should really do, or ask someone (perhaps by creating a ticket) if you don’t own the codebase. Make sure you test it first though as you don’t want the update to break your application.

Some fancy reporting (and checking license compliance) is only available in the paid plan but the basic version does a decent job too.

You can set up periodic tests with desired frequency (daily or weekly) which technically counts as continuous monitoring but it’s only the second best option compared to performing tests in your deployment pipeline. Integrating Snyk in your CI/CD workflow allows to prevent issues in your code before it even gets deployed. This is especially useful in organisations where code gets deployed multiple times a day with new (potentially vulnerable) libraries being introduced. And that’s something we are going to discuss in my next blog.

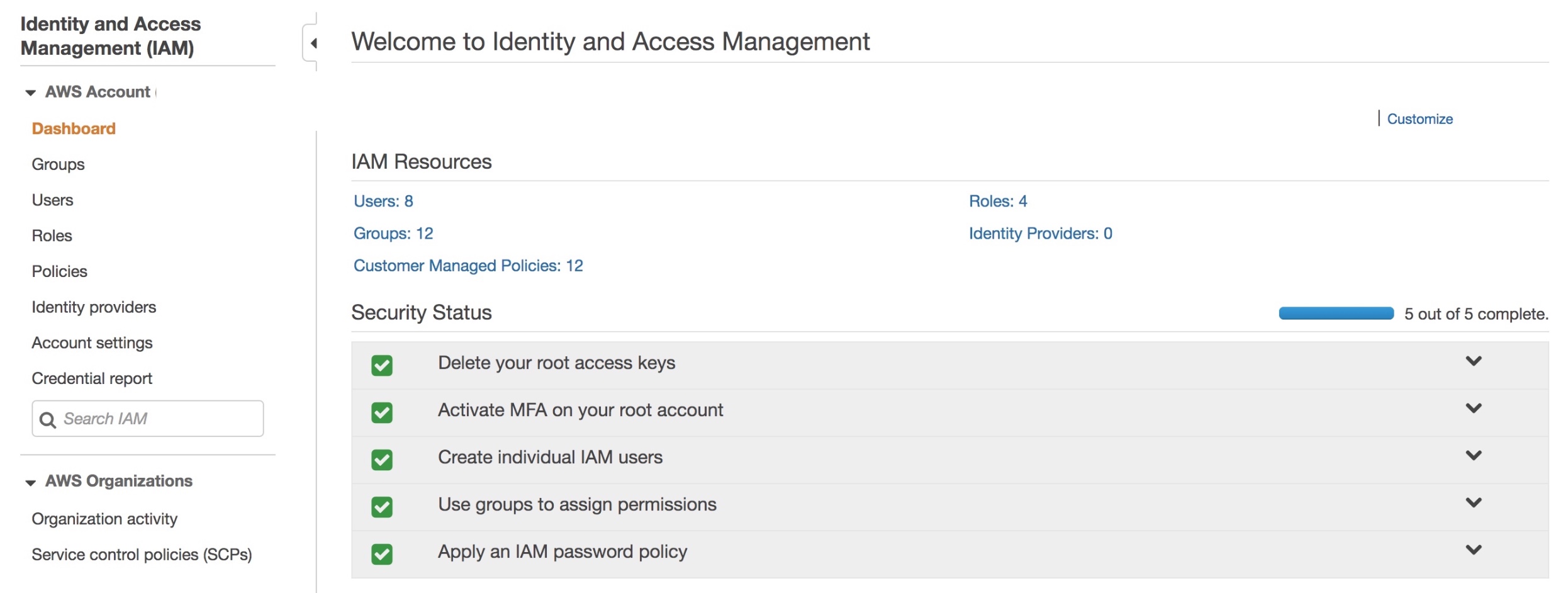

AWS security fundamentals: IAM

Here I am going to build on my previous blog of inventorying AWS accounts and talk about identity and access management. By now you have probably realised that your organisation, depending on its size, has more accounts with a lot of associated resources than you initially thought. The way users are created and access is managed in these accounts has a direct impact on the overall security of your infrastructure.

What accounts should your company have? Well it really depends on the nature of your organisation but I tend to see the following pattern for software development driven companies:

1. Organisation root. Your organisation root account should be used to create other accounts (and some other limited amount of operations) and otherwise shouldn’t be touched. Secure the credentials and leave it alone. It should not have any resources associated with it.

2. Identity. Not strictly necessary to have a separate account for this but isn’t it great to be able to manage all your users in a single account?

3. Operations. This account should be used for log collection and analysis. Your security team will be happy.

4, 5 and 6. A separate account for your development, staging and production environments. It’s a good idea to separate them for the ease of managing permissions and pleasing auditors.

Users and services that are managed within an AWS account, should only get access to what they need.

Security specialists are spending a great deal of their time reviewing firewall rules when working on their on-premise infrastructure to ensure they are not too permissive. When we move to the cloud, these rules look somewhat different but their importance has only increased.

To demonstrate the relationship between accounts, users, groups, roles and permissions, let’s walk through an example scenario of a developer in your company requiring read only access to the staging environment.

No automation or anything even remotely advanced is going to be discussed here as we are just covering the basics in this blog. It is no less important, however, to get these right. The principles discussed here will lay the foundation for more advanced concepts. Again, the terminology here is specific to AWS but overarching principles can be applied to any cloud environment.

To start with this scenario, let’s create a custom role CompanyReadOnly and attach an AWS managed ReadOnlyAccess policy in the Permissions tab.

| Role | Policies |

| CompanyReadOnly | ReadOnlyAccess |

This role allows a trusted entity (an account in this case) to access this account. When you access this account you will get the permissions defined in the policy.

Let’s say we have an account where all users are managed (the Identity account in point 2 in the list above). In this account, create a custom policy CompanyAssumeRoleStagingReadOnly allowing assuming the right role, where 123456789012 is Staging account ID which is the trusted entity for the Identity account:

{ "Version": "2012-10-17", "Statement": [ { "Effect": "Allow", "Action": "sts:AssumeRole", "Resource": "arn:aws:iam::123456789012:role/CompanyReadOnly" } ] }

Now let’s create a custom StagingReadOnly group and attach the above policy in the Permission tab.

| Group | Permissions |

| StagingReadOnly | CompanyAssumeRoleStagingReadOnly |

Finally add a user to that group:

| User | Group | Permissions |

| Developer | StagingReadOnly | CompanyAssumeRoleStagingReadOnly |

In this group additional permissions can be added, e.g. AWS managed enforce-mfa policy for mandatory multi-factor authentication.

Of course, granular policies specifying access to particular services rather than blanket ReadOnly is preferred. Remember the aim here is to demonstrate IAM fundamental principles rather than recommend specific approaches you should use. The policies will depend on the AWS resources your organisation actually uses.

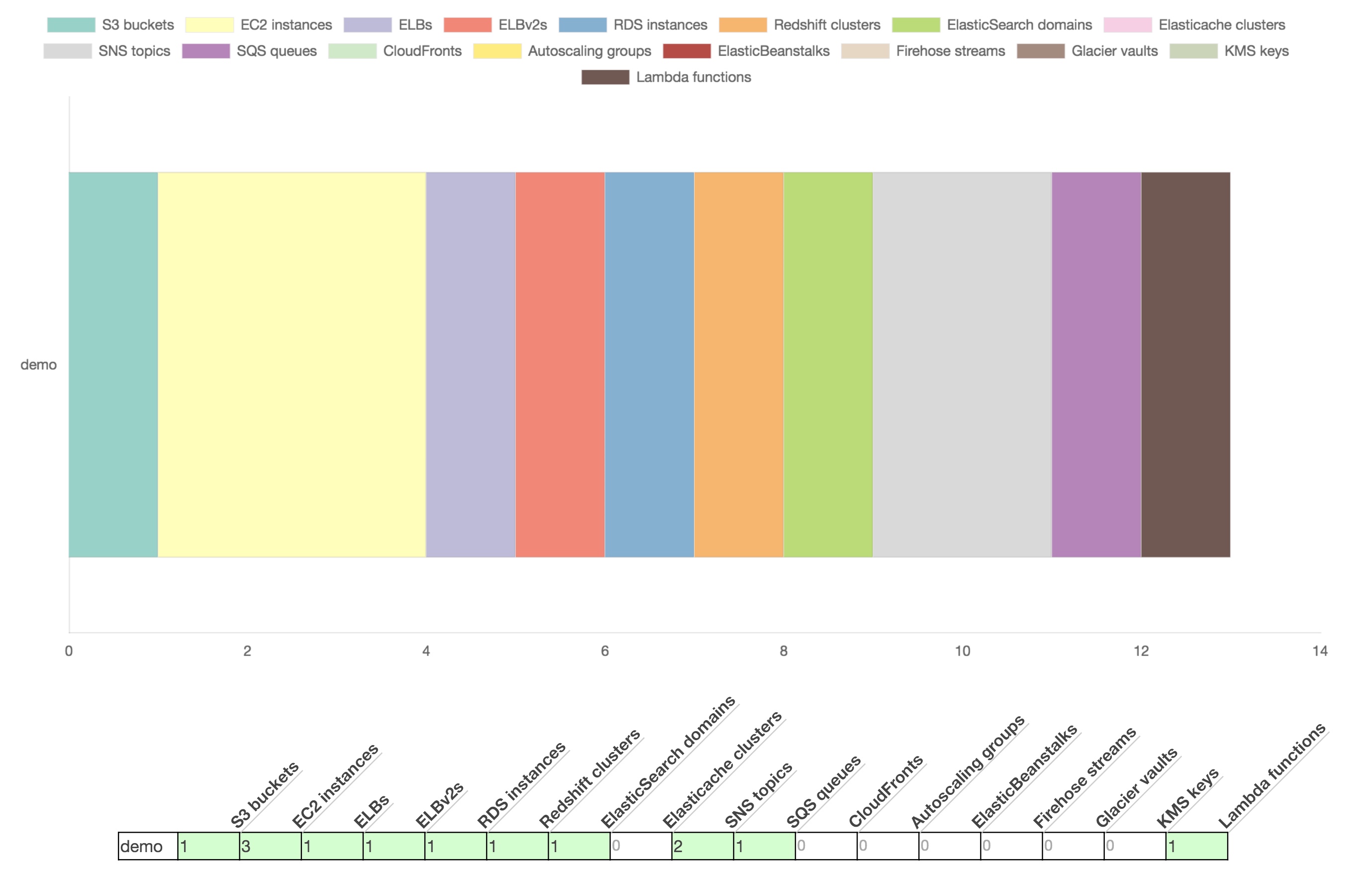

How to inventory your AWS assets

Securing your cloud infrastructure starts with establishing visibility of your assets. I’ll be using Amazon Web Services (AWS) as an example here but principles discussed in this blog can be applied to any IaaS provider.

Speaking about securing your AWS environment specifically, a good place to start is the AWS Security Maturity Roadmap by Scott Piper. He suggests identifying all AWS accounts in your organisation as a first step in your cloud security programme.

Following Scott’s guidance, it’s a good idea to check in with your DevOps team and/or Finance to establish what accounts are being used in your company. Capture this information in a spreadsheet, documenting account name, ID, description and an owner at a minimum. You can expand on this in the future to track compliance with baseline requirements (e.g. enabling CloudTrail logs).

Once we have a comprehensive view of the accounts used in the organisation, we need to find out what resources these accounts use and how they are configured. The simplest way is perhaps to use the AWS Config service. But if you want more detail (and service coverage), you can get metadata about the accounts using CloudMapper’s collect command. CloudMapper is a great open source tool and can do much more than that. It deserves a separate blog, but for now just check out setup instructions on its GitHub page and Scott’s detailed instructions on using the collect command.

The CloudMapper report will reveal the resources you use in all the regions (the image at the top of this blog is from the demo data). This can be useful in scenarios where employees in your company might test out new services and forget to switch them off or nobody knows what these services are used for to begin with. In either case, the company ends up paying for these, so it makes economic sense to investigate, and disabling them will also reduce the attack surface.

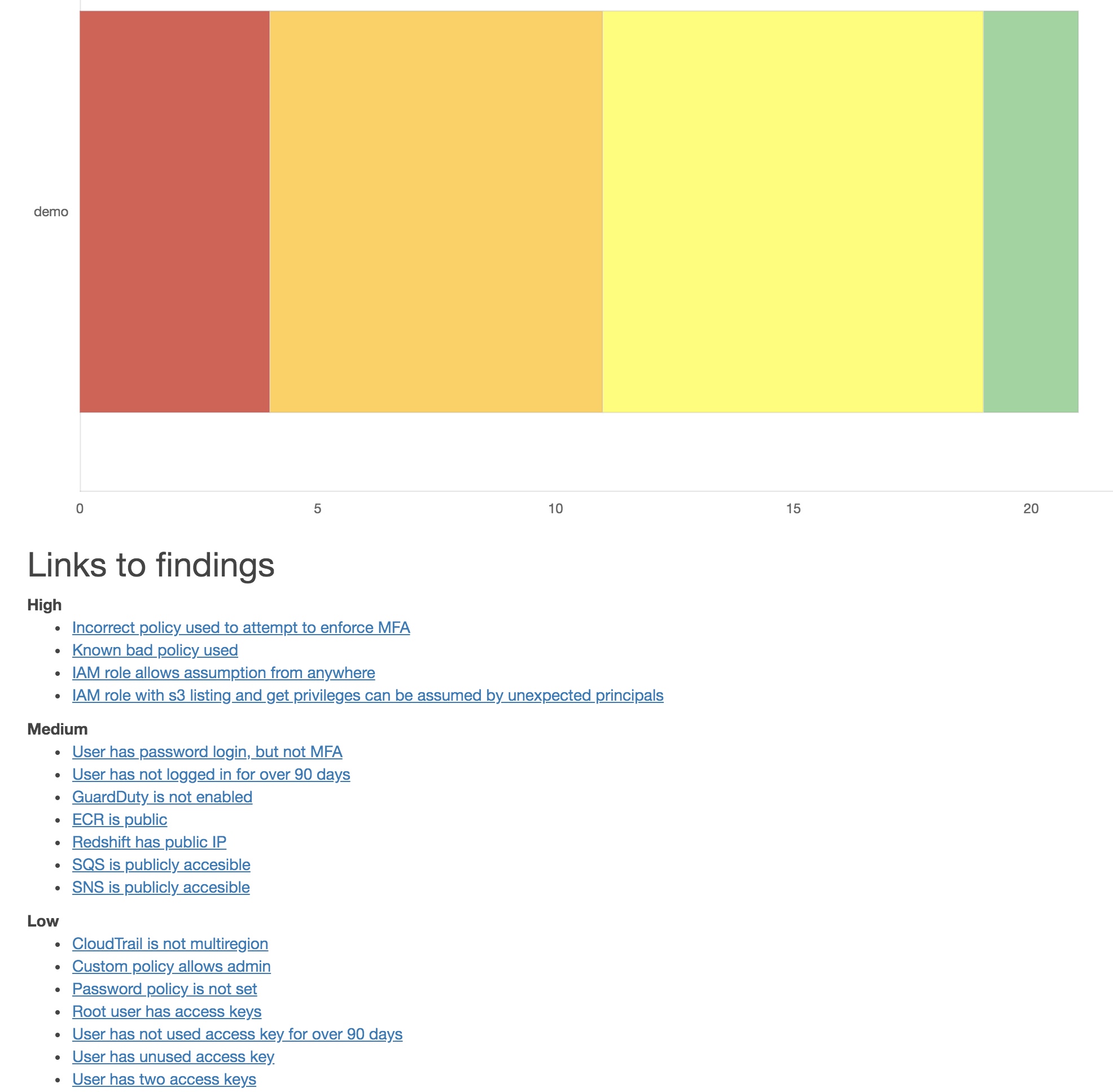

In addition to that, the report includes a section on security findings and will alert of potential misconfigurations on the account. It also provides recommendations on how to address them. Below is an example report based on the demo data.

As we are just establishing the view of our assets in AWS at this stage, we are not going to discuss remediation activities in this blog. We will, however, use this report to understand how much work is ahead of us and prioritise accordingly.

Of course, it is always a good idea to tackle high criticality issues like publicly exposed S3 buckets with sensitive information but don’t get discouraged by a potentially large number of security findings. Instead, focus on strategic improvements that will prevent these issues from happening in the future.

To lay the foundation for a security improvements programme at this point, I suggest adding all the identified accounts to an AWS Organisation if you haven’t already. This will simplify account management and billing and allow you to apply organisation-wide service control policies.

Security product management

In one of my previous blogs I wrote about building a security startup. Here I would like to elaborate on the product management aspect of a venture.

There are many businesses springing up in the cybersecurity space at the moment. A lot of them are developed by great technologists yet still struggle. The market conditions might be right and the product itself can be secure but it often fails to get traction.

When I’m asked why this might be and what to do about it, my immediate response is to dive deeper and understand the product management function.

In truth, it’s not enough to have a technically flawless solution, it has to align with what your customers want. Moreover, the bar in new product adoption is high. As Nir Eyal famously pointed out in his book Hooked, “for new entrants to stand a chance, they can’t just be better, they must be nine times better … because old habits die hard and new products or services need to offer dramatic improvements to shake users out of old routines. Products that require a high degree of behaviour change are doomed to fail even if the benefits of using the new product are clear and substantial.”

Thankfully, it’s not all doom and gloom – there are things you can do to overcome this challenge.

Depending on the stage of your venture, the most important question to answer is: are people using your product? If not, get to the point where customers are using your product as fast as you can. Then talk to them and learn from them. Find out what problem they are trying to solve.

Provide that solution and measure what matters (revenue, returning usage, renewal rate) and build measurement targets and mechanisms into your specifications.

Disciplined product management is there to bridge the gap between business (sales and marketing) and technology teams. As a product manager, you should support these teams with market analysis, planning, prioritisation, design and measurement based on customer feedback.

Knowledge of the customer and their needs will help define your strategic position and overarching guiding principles to support decision-making in the company.

That strategy in turn should be supported by tactical steps to achieve the vision. We are now beginning to shape actual work deliverables and help the technology teams prioritise them in your development sprints.

Principles described here are applicable in any type of organisation, it doesn’t have to be security specific. The industry you are in matters less than the company culture.

People often focus on tools when talking about product management or adopting agile development. The reality is that it’s often about the culture of collaboration. Break the silos, make sure customer feedback is guiding the development and don’t lose sight of the strategy. Your customers will love it, I promise.

GITEX Technology Week in Dubai

I travelled to Dubai to attend the GITEX conference this year. The scope and scale of this technology event is vast. It covers all things tech with a focus on innovation, including artificial intelligence, 5G, smart cities, future mobility and much more.

It was interesting to attend talks and participate in workshops, as well as just walk the floor to better understand current technology trends.

Of course, there was also time to explore Dubai and enjoy the many things this city has to offer.