Thank you to everyone who stopped by the book signing. It was a pleasure to meet readers and hear your thoughts. If you missed it, you can still get the book on Amazon:

https://a.co/d/0fai5zyh

A practical approach

Thank you to everyone who stopped by the book signing. It was a pleasure to meet readers and hear your thoughts. If you missed it, you can still get the book on Amazon:

https://a.co/d/0fai5zyh

Security failures are rarely a technology problem alone. They’re socio-technical failures: mismatches between how controls are designed and how people actually work under pressure. If you want resilient organisations, start by redesigning security so it fits human cognition, incentives and workflows. Then measure and improve it.

Apply simple behavioural-science tools to reduce errors and increase adoption:

A reporting culture requires psychological safety.

Stop counting clicks and start tracking signals that show cultural change and risk reduction:

Always interpret in context: rising near-miss reports with falling latency can be positive (visibility improving). Review volume and type alongside latency before deciding.

If rate rises sharply with no matching incident reduction, validate whether confusion is driving questions (update docs) or whether new features need security approvals (streamline process).

An increase may signal stronger capability and perceived efficacy of security actions. While a decrease indicates skills gaps, tooling or access friction or perception that actions don’t lead to change.

Metrics should prompt decisions (e.g., simplify guidance if dwell time on key security pages is low, fund an automated patching project if mean time to remediate is unacceptable), not decorate slide decks.

Treat culture change like product development: hypothesis → experiment → measure → adjust. Run small pilots (one business unit, one workflow), measure impact on behaviour and operational outcomes, then scale the successful patterns.

When security becomes the way people naturally work, supported by defaults, fast safe paths and a culture that rewards reporting and improvement, it stops being an obstacle and becomes an enabler. That’s the real return on investment: fewer crises, faster recovery and the confidence to innovate securely.

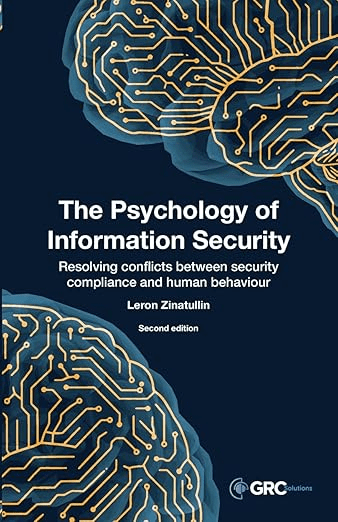

If you’d like to learn more, check out the second edition of The Psychology of Information Security for more practical guidance on building a positive security culture.

As AI adoption accelerates, leaders face the challenge of setting clear boundaries, not only around what AI should and shouldn’t do, but also around who holds responsibility for its oversight.

It was great to share my thoughts and answer audience questions during this panel discussion.

Governance must be cross-functional: security, risk, data and the business share accountability. I also reinforced the importance of guardrails, particularly forAgentic AI: automate low-risk work, but keep humans in the loop for decisions that affect safety, rights or reputation. Classify models and agents by impact and apply controls accordingly.

I recently presented on how supplier relationships shape cybersecurity risk and why that risk ultimately becomes a reputational and trust challenge for organisations of every size and sector. Below is a summary of the most important lessons I shared, plus practical next steps security leaders can apply today.

I’m proud to share that I’ve completed SANS’s LDR553: Cyber Incident Management hands-on training and earned the GIAC Cyber Incident Leader (GCIL) certification.

This course sharpened my ability to guide teams through every stage of a breach. I was awarded a challenge coin for the top score in the final capstone project.

Scenario analysis is a powerful tool to enhance strategic thinking and strategic responses. It aims to examine how our environment might play out in the future and can help organisations ask the right questions, reduce biases and prepare for the unexpected.

What are scenarios? Simply put, these are short explanatory stories with an attention- grabbing and easy-to-remember title. They define plausible futures and often based on trends and uncertainties.

I recently had a chance to share my views on cybersecurity frameworks with one of the online publications. In this blog, I provide a brief summary of key insights.

NIST released a new version of the Cybersecurity Framework with a few key changes:

I often use this framework to develop and deliver information security strategy. Although, other methodologies exist, I find its layout and functions facilitate effective communication with various stakeholder groups, including the Board.

Not every conversation a CISO is having with the Board should be about asking for a budget increase or FTE uplift. On the contrary, with the squeeze on security budgets, it can be an opportunity to demonstrate how you do more with less.

To demonstrate business value and achieve desired impact, a CISO’s cyber security strategy should go beyond cyber capability uplift and risk reduction and also improve cost performance.

Security leaders don’t have unlimited resources. Significant security transformation, however, can be achieved leveraging existing investment and security resource levels.