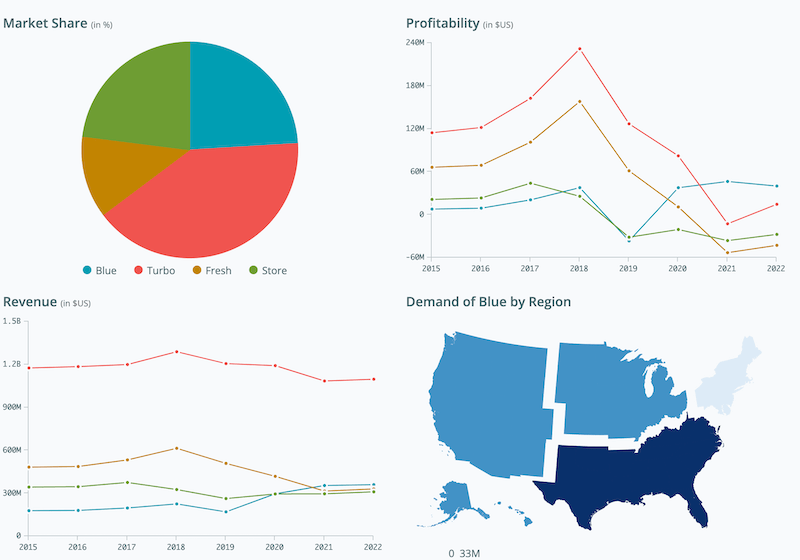

I completed the Data Analytics and Decision Making course as part of my Executive MBA. In this blog, I summarise some of the insights and learnings that you can apply in your work too.

A practical approach

I completed the Data Analytics and Decision Making course as part of my Executive MBA. In this blog, I summarise some of the insights and learnings that you can apply in your work too.

I’ve been invited to to share my thoughts on human-centric security at the Macquarie University Cyber Security Industry Workshop.

Drawing on insights from The Psychology of Information Security and my experience in the field, I outlined some of the reasons for friction between security and business productivity and suggested a practical approach to a building a better security culture in organisations.

It was great to be able to contribute to the collaboration between the industry, government and academia on this topic.

I recently had a chance to collaborate with researchers at The Optus Macquarie University Cyber Security Hub. Their interdisciplinary approach brings industry practitioners and academics from a variety of backgrounds to tackle the most pressing cyber security challenges our society and businesses face today.

Both academia and industry practitioners can and should learn from each other. The industry can guide problem definition and allow access to data, but also learn to apply the scientific method and test their hypotheses. We often assume the solutions we implement lead to risk reduction but how this is measured is not always clear. Designing experiments and using research techniques can help bring the necessary rigour when delivering and assessing outcomes.

I had an opportunity to work on some exciting projects to help build an AI-powered cyber resilience simulator, phone scam detection capability and investigate the role of human psychology to improve authentication protocols. I deepened my understanding of modern machine learning techniques like topic extraction and emotion analysis and how they can be applied to solve real world problems. I also had a privilege to contribute to a research publication to present our findings, so watch this space for some updates next year.

I’ve been exploring the current application of machine learning techniques to cybersecurity. Although, there are some strong use cases in the areas of log analysis and malware detection, I couldn’t find the same quantity of research on applying AI to the human side of cybersecurity.

Can AI be used to support the decision-making process when developing cyber threat prevention mechanisms in organisations and influence user behaviour towards safer choices? Can modelling adversarial scenarios help us better understand and protect against social engineering attacks?

To answer these questions, a multidisciplinary perspective should be adopted with technologists and psychologists working together with industry and government partners.

While designing such mechanisms, consideration should be given to the fact that many interventions can be perceived by users as negatively impacting their productivity, as they demand additional effort to be spent on security and privacy activities not necessarily related to their primary activities [1, 2].

A number of researchers use the principles from behavioural economics to identify cyber security “nudges” (e.g. [3], [4]) or visualisations [5,6]. This approach helps them make better decisions and minimises perceived effort by moving them away from their default position. This method is being applied in the privacy area, for example for reduced Facebook sharing [7] and improved smartphone privacy settings [8]. Additionally there is greater use of these as interventions, particularly with installation of mobile applications [9].

The proposed socio-technical approach to the reduction of cyber threats aims to account for the development of responsible and trustworthy people-centred AI solutions that can use data whilst maintaining personal privacy.

A combination of supervised and unsupervised learning techniques is already being employed to predict new threats and malware based on existing patterns. Machine learning techniques can be used to monitor system and human activity to detect potential malicious deviations.

Building adversarial models, designing empirical studies and running experiments (e.g. using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk) can help better measure the effectiveness of attackers’ techniques and develop better defence mechanisms. I believe there is a need to explore opportunities to utilise machine learning to aid the human decision-making process whereby people are supported by, and work together with, AI to better defend against cyber attacks.

We should draw upon participatory co-design and follow a people-centred approach so that relevant stakeholders are engaged in the process. This can help develop personalised and contextualised solutions, crucial to addressing ethical, legal and social challenges that cannot be solved with AI automation alone.

One of the UK’s leading research-intensive universities has selected The Psychology of Information Security to be included in their flagship Information Security programme as part of their ongoing collaboration with industry professionals.

Royal Holloway University of London’s MSc in Information Security was the first of its kind in the world. It is certified by GCHQ, the UK Government Communications Headquarters, and taught by academics and industrial partners in one of the largest and most established Information Security Groups in the world. It is a UK Academic Centre of Excellence for cyber security research, and an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Centre for Doctoral Training in cyber security.

Researching and teaching behaviours, risk perception and decision-making in security is one of the key components of the programme and my book is one of the resources made available to students.

“We adopted The Psychology of Information Security book for our MSc in Information Security and have been using it for two years now. Our students appreciate the insights from the book and it is on the recommended reading list for the Human Aspects of Security and Privacy module. The feedback from students has been very positive as it brings the world of academia and industry closer together.”

Dr Konstantinos Mersinas,

Director of Distance Learning Programme and MSc Information Security Lecturer.

Thank you for visiting my website. I’m often asked how I started in the field and what I’m up to now. I wrote a short blog outlining my career progression.

I’ve been asked to join PigeonLine – Research-AI as a Board Advisor for cyber security. I’m excited to be able to contribute to the success of this promising startup.

PigeonLine is a fast growing AI development and consulting company that builds tools to solve common enterprise problems. Their customers include the UAE Prime Ministers Office, the Bank of Canada, the London School of Economics, among others.

Building accessible AI tools to empower people should go hand-in-hand with protecting their privacy and preserving the security of their information.

I like the company’s user-centric approach and the fact that data privacy is one of their core values. I’m thrilled to be part of their journey to push the boundaries of human-machine interaction to solve common decision-making problems for enterprises and governments.

I was asked to deliver a keynote in Germany at the Security Transparent conference. Of course, I agreed. Transparency in security is one of the topics that is very close to my heart and I wish professionals in the industry not only talked about it more, but also applied it in practice.

Back in the old days, security through obscurity was one of the many defence layers security professionals were employing to protect against attackers. On the surface, it’s hard to argue with such a logic: the less the adversary knows about our systems, the less likely they are to find a vulnerability that can be exploited.

There are some disadvantages to this approach, however. For one, you now need to tightly control the access to the restricted information about the system to limit the possibility of leaking sensitive information about its design. But this also limits the scope for testing: if only a handful of people are allowed to inspect the system for security flaws, the chances of actually discovering them are greatly reduced, especially when it comes to complex systems. Cryptographers were among the first to realise this. One of Kerckhoff’s principles states that “a cryptosystem should be secure even if everything about the system, except the key, is public knowledge”.

Modern encryption algorithms are not only completely open to public, exposing them to intense scrutiny, but they have often been developed by the public, as is the case, for example, with Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). If a vendor is boasting using their own proprietary encryption algorithm, I suggest giving them a wide berth.

Cryptography aside, you can approach transparency from many different angles: the way you handle personal data, respond to a security incident or work with your partners and suppliers. All of these and many more deserve attention of the security community. We need to move away from ambiguous privacy policies and the desire to save face by not disclosing a security breach affecting our customers or downplaying its impact.

The way you communicate internally and externally while enacting these changes within an organisation matters a lot, which is why I focused on this communication element while presenting at Security Transparent 2019. I also talked about friction between security and productivity and the need for better alignment between security and the business.

I shared some stories from behavioural economics, criminology and social psychology to demonstrate that challenges we are facing in information security are not always unique – we can often look at other seemingly unrelated fields to borrow and adjust what works for them. Applying lessons learned from other disciplines when it comes to transparency and understanding people is essential when designing security that works, especially if your aim is to move beyond compliance and be an enabler to the business.

Remember, people are employed to do a particular job: unless you’re hired as an information security specialist, your job is not to be an expert in security. In fact, badly designed and implemented security controls can prevent you from doing your job effectively by reducing your productivity.

After all, even Kerckhoff recognised the importance of context and fatigue that security can place on people. One of his lesser known principles states that “given the circumstances in which it is to be used, the system must be easy to use and should not be stressful to use or require its users to know and comply with a long list of rules”. He was a wise man indeed.

I’ve previously written about open online courses you can take to develop your skills in user experience design. I’ve also talked about how this knowledge can be used and abused when it comes to cyber security.

If you want to build a solid foundation in interaction design, I recommend The Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. This collection of open source textbooks cover the design of interactive products, services, software and many many more.

And while you’re on the website, check out another free and insightful book on gamification. Also on offer you’ll find free UX Courses.

I’m proud to be one of the contributors to the newly published Cyber Security: Law and Guidance book.

Although the primary focus of this book is on the cyber security laws and data protection, no discussion is complete without mentioning who all these measures aim to protect: the people.

I draw on my research and practical experience to present a case for the new approach to cyber security and data protection placing people in its core.

Check it out!